In addition to repression in urban areas, the Brazilian dictatorship also had a repressive arm in the vastness of the Center-West and the Amazon through its "civilizing" project. The construction of the Trans-Amazonian highway, infrastructure projects and the expansion of the agricultural-livestock frontier generated massacres and forced displacements. Institutions such as the National Indian Foundation and the Krenak Indigenous Agricultural Reformatory deepened the dispossession. Half a century later, the National Truth Commission opens a new horizon for justice and reparation.

During the years of lead, as the military dictatorship in Brazil (1964-1985) was called, a lesser-known battle was fought far from the urban centers and the headlines. In the vastness of the Midwest and the Amazon, Indigenous people found themselves at the epicenter of a national project aimed at occupying and developing these “empty frontiers”. However, this progress came at a high cost.

The National Truth Commission’s investigation into violations committed against Indigenous peoples during the military dictatorship sheds light on a dark page in Brazil’s history. It reveals not only the depth of the injustices suffered, but also the strength of Indigenous people’s resistance. The struggle for justice and reparations is a long one and requires the continued commitment of the State and society to recognize and value cultural diversity and Indigenous rights as pillars of a full democracy.

The policy of “Security and Development

With the beginning of the dictatorship, the National Security Doctrine emerged as the ideological basis for justifying state control and repression of movements considered subversive. At the same time, the regime adopted a development policy aimed at the economic transformation of the country, with special attention to the “empty frontiers” of the Amazon and the Center-West. These regions, rich in resources and considered strategic for national security, became the target of a series of infrastructure and colonization projects. A new wave of “civilization” began. The result was a large-scale massacre and the violation of Indigenous people’s rights.

Paradoxically, in 1967 the National Indian Foundation (Fundação Nacional do Índio – FUNAI) was created with the objective of reforming the Indigenous people’s administration, replacing the former Indian Protection Service (Serviço de Proteção aos Índios -SPI), considered a corrupt organization that did not respect the rights and interests of Indigenous Peoples. Far from improving the situation, FUNAI intensified repression with the militarization of the Indigenous Posts, imposing strict control over Indigenous people’s movements within their own lands.

The objective was to provide support to Indigenous people, including health, education and technical assistance. However, they became instruments of state control, applying rigid and authoritarian discipline. This model of administration not only impeded Indigenous people’s free movement on their own lands, but also subjected their lives to constant surveillance, restricting their cultural, social and economic practices. The policies implemented in these posts reflected a paternalistic and assimilationist vision, which saw Indigenous culture as an obstacle to progress that had to be overcome.

Jader Figueiredo Correa’s 1968 report revealed widespread violations of Indigenous people’s rights, including massacres, torture and forced displacement.

Strict control of Indigenous people’s movements manifested itself in practices such as requiring permits to travel outside Indigenous people’s territories, restrictions on the performance of traditional rituals and ceremonies, and the imposition of non-traditional agricultural practices. These measures not only violated Indigenous Peoples’ fundamental rights to freedom and self-determination, but also contributed to weakening their social and cultural structures.

Jader Figueiredo Correa’s 1968 report revealed widespread violations of Indigenous peoples’ rights, including massacres, torture and forced displacement. The report, written by then prosecutor Jader de Figueiredo Correia, shows the “genocidal and unpunished actions of the Brazilian state”.

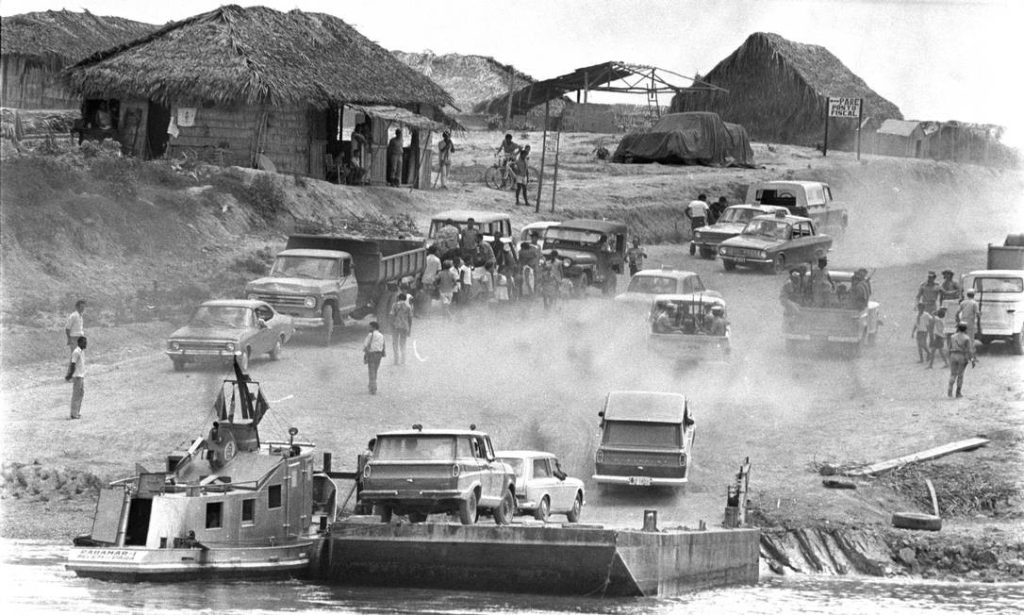

Megaprojects under the shadow of the dictatorship: between development and extermination

During the “Brazil Power” era, under the military dictatorship, the country embarked on the implementation of mega development projects aimed at occupying and economically exploiting remote regions, especially in the Amazon, known by the regime as the “green desert”. One of the main pillars of this initiative was the launching, in 1970, of the National Integration Program (Programa de Integração Nacional –PIN), which proposed the construction of highways and colonization projects, the Trans-Amazonian Highway (BR-230) being one of the most emblematic. This highway, which was to cover some 4,000 kilometers and cross states such as Amazonas, Roraima, Pará, Acre, Rondônia, Maranhão and Tocantins, was intended to integrate the isolated regions of the Amazon with the rest of the country.

However, the implementation of the Transamazonas and other similar projects has had a profound and devastating impact on the Indigenous people who have inhabited these areas for centuries. The construction of these infrastructures not only caused significant environmental devastation, but also promoted the forced displacement of numerous Indigenous populations, often without offering any compensation or adequate resettlement support. This process symbolized the developmentalist efforts of the military regime, which, in its race for economic progress, neglected the rights and very existence of Indigenous peoples.

Testimonies of Indigenous people survivors of the time to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office denounce violent actions, such as helicopters flying over the villages with poison and bombs. The National Truth Commission estimated that these conflicts caused about 2,600 deaths. In addition, the government’s strategy of exterminating isolated Indigenous Peoples, treating them pejoratively as ” raiders” or “hostiles” to free up land for construction, resulted in high mortality rates among these populations, evidencing a policy of concealment of data and facts on the part of the regime.

The Xavante, Kadiwéu, Terena, Bororo, Guaraní-kaiowá, Kayapó and Guató peoples were significantly affected by these policies, facing forced displacement, loss of territory and serious environmental problems.

The situation of the Tenharim people exemplifies the profound impacts suffered by Indigenous people as a result of these works. The highway crossed the traditional territory of the Tenharim, causing serious environmental and socio-cultural damage. FUNAI, seeking to mitigate Indigenous people’s resistance, facilitated the advance of tractors and laborers in the region, which only aggravated the damage caused.

In addition to the Transamazonica, the Central-West region of Brazil was also the object of various projects aimed at promoting the occupation, economic exploitation and integration of the area with the rest of the country. Projects such as the Polonoroeste, colonization initiatives, the expansion of the agricultural frontier, the Cerrados Development Program (Programa de Desenvolvimento dos Cerrados – Prodecer) and the Alto Paraguay Targeted Settlement Program (Programa de Assentamento Direcionado para o Alto Paraguai – PADAP) aimed to radically transform the landscape and local society. Although these projects were not formally recognized with the same stigma as the Transamazonica, they shared the common characteristic of profoundly altering the region and impacting resident Indigenous people.

The Xavante, Kadiwéu, Terena, Bororo, Guaraní-kaiowá, Kayapó and Guató peoples were significantly affected by these policies, facing forced displacement, loss of territory and serious environmental problems. These communities, many of which continue to struggle for the demarcation of their lands and the preservation of their ways of life, symbolize the current resistance against the policies of forced assimilation and exploitation promoted during the military dictatorship. The struggle to recover and guarantee their territorial and cultural rights remains a critical issue in contemporary Brazil.

Civilization attempts for peoples considered “primitive”

The initiatives implemented by the Brazilian military government, under the pretext of “civilizing” Indigenous peoples, left painful traces of violations against the Krenak Indians, among other ethnic groups. One of these measures was the creation, in 1969, of the Krenak Indigenous Agricultural Reformatory, which functioned more like a prison than a rehabilitation institution, confining 94 individuals from 15 different ethnic groups, coming from 11 states throughout the country.

According to reports, many of the detainees did not understand the reason for their detention, and some were imprisoned for such trivial reasons as drinking alcohol or leaving their demarcated areas. These Indigenous people were subjected to a regime without trial, in which torture and forced labor were common practices, as noted by a prosecutor at the time.

These actions, far from being integrative or “civilizing”, represented attempts to subjugate and eradicate Indigenous Peoples’ cultures, leaving deep wounds that remain to this day in the memory and lives of the Indigenous Peoples affected.

Another aspect of this policy of forced assimilation was the institution of the Indigenous Rural Guard. Formed by members of the Indigenous communities themselves, this force had the mission of guarding and punishing Indigenous people themselves. The first batch of this guard was prepared by the Military Police of Minas Gerais and included 84 Indigenous people from various ethnic groups and regions of Brazil, such as the Craós (Maranhão), Xerente (Goiás), Carajás (Pará), Maxacali (Minas Gerais) and Gaviões (Tocantins). This strategy of using Indigenous people to control and punish other Indigenous people caused a deep cultural division and jeopardized the sense of community and fellowship among the various ethnic groups. This division was intensified by the government’s display of power and violence, as illustrated by a shocking photograph of an Indigenous person being beaten with a wooden stick during the graduation ceremony of the first graduating class of the Indigenous Rural Guard in Belo Horizonte, an event attended by high-ranking state authorities.

These actions, far from being integrative or “civilizing”, represented attempts to subjugate and eradicate Indigenous Peoples’ cultures, leaving deep wounds that persist to this day in the memory and lives of the Indigenous Peoples affected.

A hopeful future

In a promising step towards recognition and reparation, the Amnesty Commission of the Ministry of Human Rights marked a historic milestone by accepting, for the first time, a request for collective reparation. This pioneering action shed light on the injustices suffered by Indigenous Peoples during the military dictatorship in Brazil, especially the Krenak and Guarani-Kaiowá peoples, who suffered forced displacement and rights violations in the name of “development” and “national security.” In addition, the National Truth Commission (Comissão Nacional da Verdade – CNV) revealed that approximately 8,350 Indigenous people were killed as a result of these policies, a figure that, although alarming, is considered only a fraction of the total number of victims, given the difficulty of fully documenting the impacts suffered.

The unanimous decision recognized not only the systematic persecution carried out by the military regime, but also the abuses committed prior to the 1964 coup. Leonardo Kauer Zinn, reporting on the situation faced by the Krenak people, emphasized the seriousness of government and corporate interventions on Indigenous Peoples’ lands, which resulted in the death of community members and the expulsion of entire villages. In the specific case of the Krenak, police forces were created to persecute their members, and a reformatory was set up to detain leaders opposed to the dictatorship and to force a migration that would make their lands available for agricultural use.

This milestone in the work of the Amnesty Commission underscores the importance of the Brazilian State acknowledging the violence and injustices perpetrated against Indigenous Peoples during the dark days of the dictatorship.

It is important to note that the Amnesty Commission, in responding to these requests for collective reparations, did not envisage direct economic compensation, but recommended to the government the implementation of specific public policies. Among the measures suggested were the demarcation of lands belonging to the two ethnic groups and the strengthening of health care in Indigenous Peoples’ communities, with a view to reparation and recognition of the rights of these peoples.

This milestone in the work of the Amnesty Commission underscores the importance of the Brazilian State acknowledging the violence and injustices perpetrated against Indigenous Peoples during the dark times of the dictatorship. This step is crucial to heal the wounds left by the past, ensuring that future generations of the Krenak and Guarani-Kaiowá peoples can inhabit their ancestral lands with dignity, safety and health, honoring their cultural heritage and fundamental rights. This is a hopeful future, a sign of progress on the long road to historical justice for Brazil’s Indigenous people.

María de Lourdes Beldi de Alcantara has a degree in Social Sciences, a master's degree in Anthropology (Pontifícia Universidade de São Paulo), a PhD in Sociology (University of São Paulo) and a Post PhD in Social Psychology. Currently, she is a professor of medical anthropology at the School of Medicine of the University of São Paulo (FMUSP).