Indigenous peoples share a common goal in seeking an education that is truly our own. This education originates from our language, our worldview, and our memory. It can be explained in this way: two different cultures, occupying different geographical spaces, see the same occurrence but perceive in it different things. This pedagogy of "we" understands that everything is alive, and everything that is present is alive because it has a purpose. It recognizes that knowledge emerges when we interact harmoniously with nature. For us, the Añú people, life is rooted in sharing with others and being responsible toward one another.

In this gathering, there is a fundamental agreement in the pursuit of our own education. A Nasa companion says the meeting is more about sharing knowledge, and he is right. In the Añú language, it should be called atiyera, meaning a teach-learn relationship between two. It is never one person teaching and the other learning. It is always about sharing experiences.

At this point, we have a big problem to solve and we have limited time, but there is so much to say because our memory is long. I want to tell you that we must understand that time is not made by us. Everything that exists in the universe and in the world is alive. This is a fundamental principle of our Añu education: everything is alive, and everything that is present is alive because it has a purpose. This is more or less what the Piaroa Wötuja companion was trying to explain about what bees do and how fish behave. What does your people do to learn from bees or animals? They understand that bees are alive because they have a purpose.

The purpose of the earth is to create time. Time is not made by the men of capitalist modernity, who imposed the idea that time can be controlled, to the extent that we use clocks. If you observe it, the clock moves against the way the earth moves. That is the principle of Western public education, to teach and learn to move counter to the way the world moves. We need to understand this in order to eradicate it from our thinking. Eradicating it is not a decree; eradicating it is an experience, it is a purpose.

The plant, the ouriyakar, the tree, and the kuuncar

Another fundamental element to pay attention to is language. Memory is built in the same process as the construction of territories, so territory and memory go hand in hand. Each people name or map their territory based on how they perceive it. Let me explain it this way: two different cultures, occupying different geographical spaces, see the same landscape but perceive different things.

To illustrate, imagine we see a small plant sprouting, and in Spanish, we say “una planta” (a plant). However, as this plant grows and becomes a tree, we don’t say “la árbol” or “una árbol”; we say “el árbol” (the tree). Something remarkable happens—a transformation process in which what was born female becomes male. In Spanish, the transition from “la planta” to “el árbol” makes sense. Each language has its own logic because it responds to the thinking that generates it: language and thought, then, cannot be separated. Language is not just a means of communication; it is the thought system of the people who generate it, and these people develop that language in their relationship with space, land, and territory.

Those who speak Spanish see a plant, while the Añú see something different: we see something emerging, something sprouting, something alive. We use another fundamental word, then: doing is essential.

Those who speak Spanish see a plant, while the Añú see something different: we see something emerging, something sprouting, something alive. We use another fundamental word, then: doing is essential.

In Añú, when it’s a small plant, you should say ouriyakar. Ouriya means “emerging,” “sprouting,” and kar is the article. We speak in reverse order, not saying “la planta” (the plant), but “planta la”. So, the small plant would be the one that sprouts, that emerges, that is coming into being. However, when it’s mature, we say kuuncar. Uun means mother, and if I want to say “my mother,” I should say tuun. But kuuncar means “the one that has the property of being a mother” because indeed, it’s the trees that have the property of producing seeds, giving flowers, giving fruits. For the Añú, it’s born female and becomes an adult female; there’s no transformation because that’s our perspective.

In summary, those who speak Spanish see a plant, while the Añú see something different: we see something emerging, something sprouting, something alive. We use another fundamental word, then: doing is essential. We work based on doing because we create the territory, we build it, and this doing is thoughtful; we act thoughtfully, we create things.

Seeing the world with spirit

Knowledge is produced when we act in correspondence with Nature and the world that occupies us. Life is elemental. We need to address the act of inhabiting. We begin by teaching mathematics, but starting with the construction of the house, because the house is not only the place we inhabit or that conceals us. The house is a design, the house is a calculation, the house must be responsive to the way we understand our relationship with space. The house has to do with the materials with which we have to build it: the house must have a shape and that shape responds to what we call “eirare.

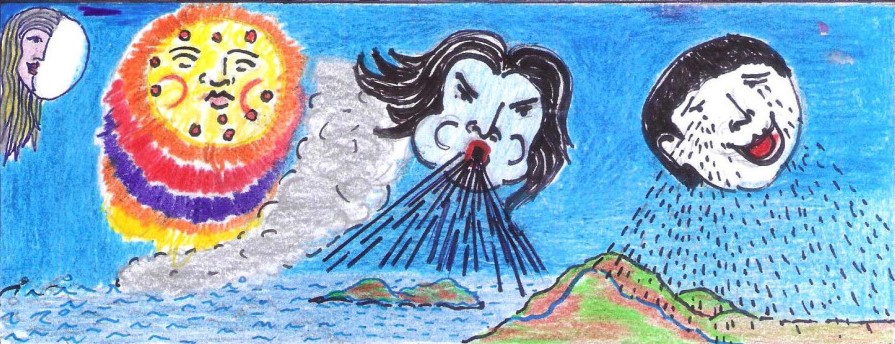

Eirare is what many call “worldview.” For us, it means “seeing the world with spirit, not with the eyes.” Western science says that only what is visible is possible and true, that which is possible to see, quantify, calculate. However, we do not see the wind and the wind is there; we feel it, we smell it, we perceive it. We also do not see viruses, but we know they exist and can be in plants, animals, and ourselves. In any case, then, not everything that is visible is true, or not everything that is not visible is not true. Simply put, it depends on a perspective, and that perspective for us is what we call worldview.

Asokuta means to respond; you must be responsible, you have to answer for everything. You answer for what you do, but also for what you fail to do; for what you say and for what you remain silent about; you answer for the fish, the trees, the mangroves.

Asokuta means to respond; you must be responsible, you have to answer for everything. You answer for what you do, but also for what you fail to do.

Finally, every process of knowledge, every educational process or sharing of creations, this act of doing, must always be related to what we call an ethical horizon, a direction toward which we want to reach. What do we want to be and what do we need? We need to address the issues of dwelling, eating, healing, and coexisting, among ourselves and with others. So, what is that horizon? For us, that horizon is what we call “ee apa” in Añú, which means “being a hand.” For the Wayúu, our neighboring brothers, it’s “wakuaipa.” They are two different things, but they resemble each other because they respond to the same principle.

Being a hand is what maternal uncles teach boys when they take them for the first time on a boat to go fishing. They hold your hand, lift your pinky finger, and say, “This is your path to becoming a man, to being a hand, and this is your first task called asokuta.” Asokuta means to respond; you must be responsible, you have to answer for everything. You answer for what you do, but also for what you fail to do; for what you say and for what you remain silent about; you answer for the fish, the trees, the mangroves. You answer for everything; you cannot deny responsibility, you cannot say “I am not responsible because I was not there.” Therefore, and this is the second finger, you must act and speak truthfully. We call this kapiya, which means something shared. There are no individual truths; it is false to say “everyone has their own truth.”

Ookoto: life, sharing, and responsibility

Something becomes true when it is shared. We might be wrong about an idea, but if we share it, it becomes true for us until we realize our mistake. I have been wrong for a long time, but by sharing, it has been true, albeit mistakenly. However, you cannot lie because the moment you lie, you are no longer responsible; you revert to the starting point. You must act truthfully, speak truthfully to be responsible. If you are truthful because you are responsible, then we call this Ke’inchi: having your heart present in everything you do and say.

Having your heart present generates trust. Trust is at the center of every community. When there is no trust, the community breaks apart. That is our current dilemma: we don’t trust each other, we don’t trust ourselves, we doubt what we can accomplish, always thinking, “Who can help me?”, ”Who will finance us?”. If we trusted our comrades and ourselves, these questions would not exist. But if we are trustworthy because we must also trust, then comes the fourth finger, which we call aürei. Aürei is the one who can give encouragement.

Life is nothing more than cutting and sharing. That’s what the comrades just did: they made juice, cut it into portions, and distributed it among everyone for that ookoto. For us, it’s a multiplier.

What does it mean to give encouragement? It means to uplift others, to breathe life into them, to generate hope and act in ways that foster hope and life. It’s like when your uncle tells you, “You’re ready to ask a girl to be your partner.” Why? Because you are reliable, truthful, and responsible. If you’re irresponsible, if you lie, if you’re untrustworthy, no woman would want to live with you, and you’ll end up alone. So, here, you are self-sufficient, you create life, you build family, you encourage family and community.

Then, the time comes when you grow old, and this is the thickest finger because it’s laden with experience. This is what we call ke’intaa Ke’intaari if it refers to a man or “Keintaarü” if it refers to a woman. It is someone who carries wisdom in their heart, gained through experience. Therefore, they become a pillar. And the other hand is never just our own; it belongs to others—your partner, your community, the fish, the plants, the bees. We call this ookoto, which means “to cut” or “to share.” Life is nothing more than cutting and sharing. That’s what the comrades just did: they made juice, cut it into portions, and distributed it among everyone for that ookoto. For us, it’s a multiplier.

Memory and the pedagogy of us

Language expresses the thought system of a people because it has been the product of a long experience of memory construction, and that memory is not just about memories. We can remember things, and memories are part of memory, but memory goes beyond that: memory is what we do even without remembering; we act in ways that we don’t recall where they come from or how we learned them. Life is lived; life is not a national constitution, life is not a system of written laws. That’s what I want you to understand, and I’m not saying we shouldn’t consider laws. I’m not saying that; rather, I’m saying we should not base our lives solely on those laws.

Education for us, as our fellow Wötuja rightly points out, should be intercultural and bilingual. Perhaps Venezuela was the first country in Latin America to initiate a process of creating an education system for Indigenous communities from an intercultural and bilingual perspective. We, the Añú people, were part of that process that led us to develop alphabets alongside a group of linguistic colleagues. During that time, our teachers created alphabets for all indigenous languages in Venezuela.

After more than 500 years of colonization and domination, Indigenous peoples have been configured and reconfigured territorially and culturally. We call the particular education of each people our own pedagogy of us.

After more than 500 years of colonization, Indigenous peoples have been configured and reconfigured territorially and culturally. We call the particular education of each people our own pedagogy of us.

However, what happened? All contents of public education were translated into Iindigenous languages, so our teachers became colonizers through their own languages. By the 1980s, a group of Indigenous intellectuals had already formed, but in the Western way. Then, a group of crazy people, like myself, said, “No, it’s not about intercultural and bilingual education.” It’s not that we don’t continue to apply interculturality, but it must be an interculturality where we are on equal footing, where what the community knows is not just ancestral knowledge. These are ideas that we always subject to debate, because when we talk about ancestral knowledge, it seems as if it were immutable knowledge. And that’s not the case.

All knowledge is transformable. After more than 500 years of colonization and domination, Indigenous peoples have been configured and reconfigured territorially and culturally. We call the particular education of each people our own pedagogy of us. This is how our uncles teach us, but women are taught differently; it’s another process, and indeed, it’s a process unknown to men. It’s an exclusive process of grandmothers with young girls, which happens when they have their first menstruation. What I do know is that my four sisters received this education, all of them living, well-placed, and situated on thier territories (and difficult, because there, women are in charge). Men are wind and breeze, women are water and earth, and therefore, they are the material and symbolic representation of the stability of life.

This article corresponds to the transcription of José Ángel Quintero Weir’s participation in the event “Amazonian Memory as the Foundation of Forest-Protecting Education,” organized by the Institute for Rural Development of South America (IPDRS) within the framework of the Pan-Amazon Social Forum (FOSPA), held in Rurrenabaque on June 14, 2024.

José Ángel Quintero Weir is a member of the Añu people of Venezuela, a professor at the University of Zulia, a promoter of the Indigenous Autonomous University (UAIN), and a member of the Intercultural Organization for Autonomous Education Wainjirawa.