In June, reports emerged about the presence of an isolated indigenous group, known as the Mashco Piro, near an indigenous community in northern Madre de Dios. Weeks later, international media outlets published images of them, highlighting the impact of logging activities on their territory. It is crucial to understand the way of life of this group and the importance of their territory, the connection between extractivism, their isolation, and the risks they face, as well as the efforts of indigenous organizations to protect them and the forests they inhabit.

The Mashco Piro are one of the largest indigenous groups living in isolation in Peru. They inhabit the southern Amazon, across the departments of Ucayali, Madre de Dios, and Cusco, extending into the forests of Acre, Brazil. Typically, they limit their interactions with outsiders and sustain themselves by hunting forest animals and birds, as well as gathering turtle eggs, fruits, and other forest resources. Their movements across their territory are highly dynamic, dictated by dry and rainy seasons. During the Amazonian summer, they extend their movements downstream, occasionally coming close to nearby indigenous communities.

The language spoken by this group is partially understood by the Yine people from nearby communities, with whom they have occasionally interacted from a distance. They are separated by the river, and only interact for short periods of time. These encounters often carry significant tension due to the unpredictability and the potential for violence. In such interactions, the Mashco Piro typically request bananas and other useful items. However, there have also been instances where they have entered community farms and taken food products.

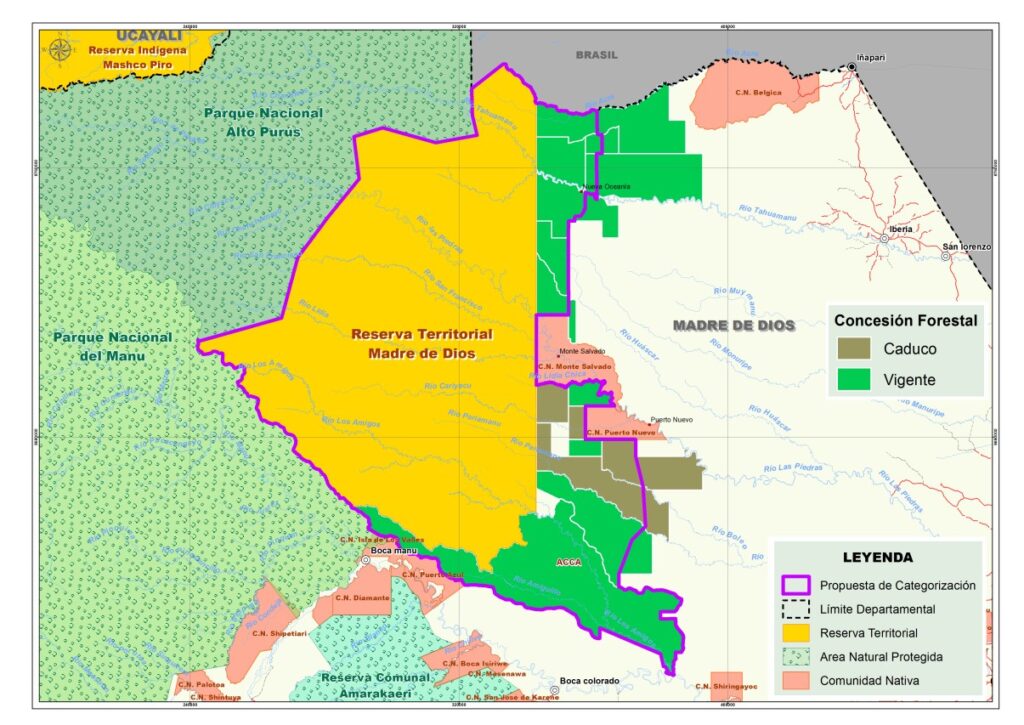

The elder members of the Yine communities have learned how to manage this tension, which is why they have been selected by the Native Federation of the Madre de Dios River and its Tributaries (FENAMAD) as well as the Ministry of Culture to serve as agents of protection for the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve, which was established to safeguard isolated peoples. The careful management of the seasonal presence of isolated groups near some communities contrasts sharply with the dangers they face in the eastern part of their territory, where the Peruvian government has granted logging concessions, prioritizing economic interests over the protection of their lives.

A long delay in expanding the reserve

In 2002, amid intense social unrest and violence fueled by logging companies, an indigenous reserve was created to protect the isolated peoples of northern Madre de Dios. While this was a significant victory for indigenous organizations, the reserve only encompassed 34% of the area identified as the territory of these peoples. More than 50% of the area was designated part of the Alto Purús Reserved Zone (now a national park) while the remainder, due to pressure from businesses and authorities, was turned into permanent forest production zones for logging.

As a result, nearly 300,000 hectares of forest within Mashco Piro territories began to experience intense, officially sanctioned logging activity, different from previous years. Consequent violent encounters between loggers and isolated indigenous groups have persisted. The inaction and silence of judicial authorities in response to formal complaints filed by FENAMAD, regarding assaults on isolated indigenous peoples have led to a request for precautionary measures before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, a request which was granted in 2007.

Studies coordinated by the Ministry of Culture reaffirmed the presence of isolated populations in the area classified as Permanent Forest Production Zones.

As of July 2024, the reserve has not yet been officially categorized or expanded and some logging companies continue to operate in this part of the territory inhabited by isolated peoples.

In 2012, the process initiated a reclassification of the Territorial Reserve as an Indigenous Reserve, in accordance with Law No. 28736 on Isolated and Initial Contact Peoples. This law was enacted in 2006. Studies coordinated by the Ministry of Culture reaffirmed the presence of isolated populations in the area classified as Permanent Forest Production Zones, just as the FENAMAD technical team had reported a decade earlier.

Subsequently, an expansion of the reserve to the east was recommended and approved in 2016 by the Multisectoral Commission responsible for the reserve’s categorization. As part of this process, a working group was formed to produce a report on the issue of overlapping forest concessions within the proposed expansion area within four months. As of July 2024, the reserve has not yet been officially categorized or expanded and some logging companies continue to operate in this part of the territory inhabited by isolated peoples.

The impact of logging activity

The presence of logging operators, their movements through the forest, the establishment of camps, waste production, the transit of vehicles and heavy machinery, the noise from machinery, as well as hunting, fishing, and gathering for daily sustenance, all have serious implications for isolated peoples. Additionally, given their lack of immune defenses and resulting high vulnerability, the presence of outsiders in their territory increases the risk of the transmisión of disease.

Environmental contamination becomes a source of infection, leading to the spread of parasitic diseases, anemia, and acute diarrhea—one of the leading causes of death among isolated and initial-contact-populations. The pressure on forest animals and fish to feed hundreds of logging workers reduces resources and creates competition with the isolated groups for whom these are the sole sources of sustenance. Moreover, the noise from logging activities scares away animals, further complicating subsistence practices.

The National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) has raised concerns about the increasing Mashco Piro population (which extends to the Brazilian side of the border) and its risky approach toward, and hostility against indigenous villages.

The National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) has raised concerns about the increasing Mashco Piro population (which extends to the Brazilian side of the border).

Simultaneously, logging activities drive the construction of roads for transporting personnel, equipment, and extracted timber. Secondary roads within logging concession areas located between the Acre and Tahuamanu rivers have a significant impact on the territories of isolated peoples. The severe disruption of soil, water, flora, and fauna fragments the territory, shrinking hunting and gathering areas. Consequently, road construction severely undermines food sources and means of subsistence, which in turn threatens the physical, territorial, and socio-cultural integrity of these groups.

In Brazil, the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) has raised concerns about the increasing Mashco Piro population (which extends to the Brazilian side of the border) and its risky approach toward, and hostility against indigenous villages. Given the isolated peoples’ need to secure subsistence sources, it is highly likely that they are seeking to compensate for the loss of vital spaces caused by logging. This situation is extremely serious and often leads to friction both within the isolated groups themselves and with loggers and neighboring indigenous communities.

The importance of protecting territorial corridors

The Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve is part of a vast expanse of continuous territories inhabited by various isolated and initial contact peoples, known as the Pano, Arawak, and Other Territorial Corridor. This corridor stretches north, south, east, and west, crossing the border into Brazil and encompassing the forests of Acre along the frontier. Further north, separated by the Amonya River, lies a second territorial corridor for isolated and initial contact peoples, known as Yavarí-Tapiche. Spanning over 25 million hectares of continuous forests, these two corridors represent the largest area in the world inhabited by isolated and initial contact peoples.

The protection of these territorial corridors is being driven by at least 50 indigenous organizations on both sides of the Peru-Brazil border. Leading this movement are the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest (Aidesep), the Regional Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the East (Orpio), and the Coordination of Indigenous Peoples of the Brazilian Amazon (Coiab). In many cases, indigenous councils made up of local and regional organizations have been established to lead efforts in formulating strategies for the protection of these territories.

The protection of these corridors requires a comprehensive approach to isolated and initial contact peoples, considering their territoriality beyond legal categories established by States.

The protection of these corridors requires a comprehensive approach to isolated and initial contact peoples, considering their territoriality beyond legal categories established by States.

The protection of these corridors requires a comprehensive approach to isolated and initial contact peoples, considering their territoriality beyond legal categories established by States. The initiative advocates for the implementation of protective policies and mechanisms for these peoples and their territories, coordinating across various government sectors and levels. Effective coordination with indigenous organizations within the reserves and their inhabited territories is essential. Given their cross-border mobility, policies with a binational perspective are also proposed.

Additionally, the initiative promotes the adoption of communal agreements to respect the ways of life and subsistence areas of isolated peoples and aims to enhance the socio-territorial governance of indigenous communities and other surrounding populations. These approaches are based on principles of respect for life, territory, self-determination, and traditional ways of living. They also include preventive measures against the impacts of sustained contact and sedentarization on their health and means of subsistence.

The protection of these corridors requires a comprehensive approach to isolated and initial contact peoples, considering their territoriality beyond legal categories established by States. The initiative advocates for the implementation of protective policies and mechanisms for these peoples and their territories, coordinating across various government sectors and levels. Effective coordination with indigenous organizations within the reserves and their inhabited territories is essential. Given their cross-border mobility, policies with a binational perspective are also proposed.

Additionally, the initiative promotes the adoption of communal agreements to respect the ways of life and subsistence areas of isolated peoples and aims to enhance the socio-territorial governance of indigenous communities and other surrounding populations. These approaches are based on principles of respect for life, territory, self-determination, and traditional ways of living. They also include preventive measures against the impacts of sustained contact and sedentarization on their health and means of subsistence.

In conclusion

Over time, the physical, socio-cultural and territorial integrity of the Mashco Piro has been severely affected by the development of extractive activities such as rubber tapping, hydrocarbon extraction, and recently, logging. These economic activities, driven by the dominant economic model, have led to the invasion of their territories, persecution, murder, slavery, the spread of epidemics, and the degradation of their sources of livelihood. The lack of legal security and territorial protection highlights the disregard for the rights of isolated peoples.

The Mashco Piro’s existence, their reliance on hunting and gathering resources from forests and rivers are closely tied to a healthy environment. Beyond its importance for the survival and continuity of isolated peoples, the forests of Madre de Dios contain crucial headwaters for the Amazon basin. These ecosystems, rich in diverse flora and fauna, have led to the establishment of prominent protected natural areas, including Alto Purús, Manu, and Sierra del Divisor National Parks.

In response to threats to the Mashco Piro and other isolated peoples posed by extractive economies, indigenous organizations have initiated efforts to safeguard their rights. They have come together to advocate for the protection of territorial corridors (or continuous territories) for isolated and initial contact peoples, extending beyond legal constraints and transcending international borders.

Note from the Editor: The article has deliberately avoided mentioning the specific locations inhabited and traversed by the Mashco Piro due to the potential risk to their safety. This precaution is taken to prevent individuals with harmful intentions from pinpointing their exact whereabouts, which could jeopardize their protection.

Beatriz Huertas Castillo is a Peruvian anthropologist specializing in isolated and initial contact peoples. As part of the technical team at Fenamad, she was responsible for conducting anthropological studies for the establishment of the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve. She currently works as a policy advisor on the protection of isolated and initial contact peoples at Rainforest Foundation Norway.