The 2008 Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador establishes Ecuador as a plurinational and intercultural country. One of the most important areas of progress has been that of recognizing Indigenous justice systems to resolve conflicts in their own territories when they affect basic principles such as ama llulla, ama killa, ama shwa and ranti ranti. Taking their own customs, law and socio-economic situation into consideration, sanctions other than imprisonment are imposed. Nevertheless, while the two justice systems should be hierarchically equal, the ordinary justice system in practice limits the powers of the Indigenous authorities while at the same time depriving more than 600 Indigenous people of their freedom.

The 2008 Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador establishes Ecuador as a plurinational and intercultural country. One of the most important areas of progress has been that of recognizing Indigenous justice systems to resolve conflicts in their own territories when they affect basic principles such as ama llulla, ama killa, ama shwa and ranti ranti. Taking their own customs, law and socio-economic situation into consideration, sanctions other than imprisonment are imposed. Nevertheless, while the two justice systems should be hierarchically equal, the ordinary justice system in practice limits the powers of the Indigenous authorities while at the same time depriving more than 600 Indigenous people of their freedom.

Following years of struggle and resistance, Ecuadorian society made two important gains: the Constitutional Reform of 1998 and the new Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador of 2008. As part of this process, the country’s Indigenous Peoples called for Ecuador to be declared a plurinational and intercultural state, and managed to get this included in the first article of the Constitution. This brings with it a recognition of plurality in all its different forms: cultural, linguistic, economic, organizational, legal, religious and political. For the first time in the country’s history, the existence of communes, communities, Indigenous Peoples and nationalities is recognized, in addition to the Afro-Ecuadorian and Montubio peoples.

The communes, communities, peoples and nationalities are also recognized as subjects and holders of constitutional rights, together with those rights set out in the different international instruments. Finally, after much debate, nature was also recognized as a subject of rights, thus breaking with the liberal paradigm that considers only individuals as rights holders, with nature being considered a mere resource.

In terms of the specific rights of Indigenous Peoples, the catalogue of collective rights that was initially recognized in the 1998 Constitution has now been expanded to land and territory, ancestral possession, ancestral medicine, collective intellectual property, protection of ancestral knowledge and the cultural heritage of Indigenous Peoples. Recognition of the right to cultural identity furthermore includes their customs, traditions and sense of belonging.

Respect for their own forms of organization and exercise of authority, together with the right to participation, is expressed in free, prior and informed consultation to obtain their consent when taking decisions affecting their territories. In addition, pre-legislative consultation requires that the State consult with the Indigenous Peoples and nationalities prior to adopting administrative and legislative regulations; failure to do so would be unconstitutional. Finally, the right to create, develop and strengthen one’s own rights is recognized.

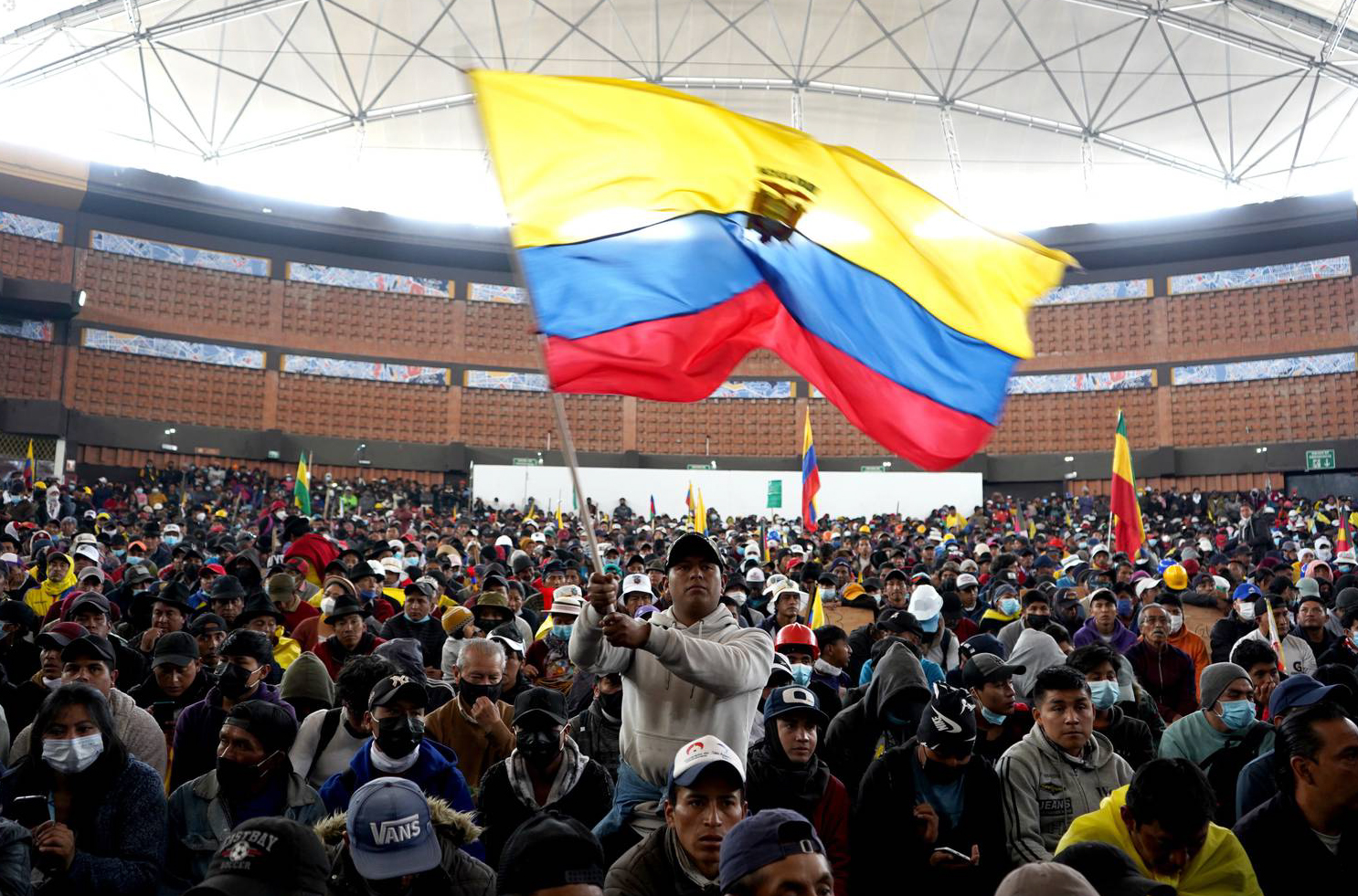

Indigenous protests in 2000 against the government of Jamil Mahuad. After years of resistance, Ecuadorian society won the Reform, the new Constitution of the Republic in 2008. Photo: El Universo

Indigenous protests in 2000 against the government of Jamil Mahuad. After years of resistance, Ecuadorian society won the Reform, the new Constitution of the Republic in 2008. Photo: El Universo

Indigenous justice system

The Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador recognizes jurisdictional functions to the authorities of communes, communities, Indigenous Peoples and nationalities. It thus grants them competence and jurisdiction to resolve internal conflicts within their territories (llaki-llakikuna) when they affect basic principles such as ama llulla, ama killa, ama shwa (not to lie, not to be lazy, not to steal) or ranti ranti (reciprocity and solidarity), all of which result in disharmony between individuals or with nature. Customs, rules, principles, procedures and sanctions are applied to guarantee women’s participation.

One limit that is set by the Constitution, both for the Indigenous and ordinary justice systems, is that they must show strict respect for the human rights recognized in international instruments. The decisions adopted by the authorities of the Indigenous jurisdiction likewise also constitute res judicata, and must therefore be respected by all public institutions and authorities. Finally, the only body with the capacity to conduct constitutional control when circumstances so demand is the Constitutional Court.

This means that the Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador recognizes the Indigenous justice system on an equal footing with the ordinary justice system. Only their operating dynamics, philosophies, cultural codes, worldviews and conflict resolution procedures differ, each of them responding to the wealth of Indigenous diversity. It is important to note that this legal pluralism cannot be reduced simply to the validity of the Indigenous justice and ordinary justice systems since there lies a true legal pluralism within Indigenous justice due to the lack of homogeneous peoples and nationalities.

The Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador recognizes the Indigenous justice system on an equal footing with the ordinary justice system.

The Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador recognizes the Indigenous justice system on an equal footing with the ordinary justice system.

The constitutional recognition of legal pluralism has undoubtedly made it possible for Indigenous Peoples to exercise this collective right with greater force. It has also required a strengthening of communal governments, territorial authorities and harmonious coexistence between humans and nature. The Indigenous authorities have thus been resolving both disagreements between individuals as well as collective conflicts with the State.

Indigenous justice forms part of the Indigenous Peoples’ way of life: it is not activated merely when there are conflicts but seeks to improve living conditions as part of the governance of the peoples themselves. With the aim of organizing and safeguarding the life of future generations, it has been decided through the Indigenous justice system and by collective decision to declare certain territorial spaces the inalienable patrimony of the peoples and for the protection of water. Since these are areas where the rivers and streams rise, they have been considered free from mining and other extractive activities.

Indigenous justice seeks to safeguard the principles of ama llulla, ama killa, ama shwa (do not lie, do not be lazy, do not steal) and ranti ranti (reciprocity and solidarity). Photo: CONAIE

Indigenous justice seeks to safeguard the principles of ama llulla, ama killa, ama shwa (do not lie, do not be lazy, do not steal) and ranti ranti (reciprocity and solidarity). Photo: CONAIE

Delegitimization and attacks on the Indigenous justice system

Notwithstanding this constitutional progress, exercise of this right has not been an easy task since it has run into several problems that have not yet been overcome in these almost 14 years of validity. The State and civil society have challenged the Indigenous justice system in various ways: that it is an invention, that it is a step backwards, that there are no procedures, that due process is not respected and that the sanctions (the “fuete”, the cold water bath or nettle bath) are in violation of human rights and are expressions of savagery. These criticisms come from a monistic point of view, that is, from the preeminence of a single justice system.

It has also been pointed out that the Indigenous justice authorities are not properly prepared because they have no academic training and should therefore restrict themselves to solving small problems or petty crimes. According to this view, they should not resolve cases of domestic violence because it is believed that violence against women is a cultural phenomenon in the Indigenous world. These interpretations ignore and overlook the fact that misogyny in the Indigenous territories has precisely been inherited from a colonialism that transcends all societies.

The Indigenous authorities have had to face ongoing delegitimization of their capacity to exercise justice.

The Indigenous authorities have had to face ongoing delegitimization of their capacity to exercise justice.

As can be seen, the Indigenous authorities have had to face ongoing delegitimization of their capacity to exercise justice. These attacks arise from the State’s disregard for the decisions passed down by the Indigenous justice system and this has, in a number of cases, resulted in double jeopardy. In addition, the criminalization of the authorities for exercising their right to impart justice, through the inappropriate use of criminal classifications, has resulted in judgments that are totally alien to their cultural reality and has been aimed at creating fear.

This situation has forced peoples and nationalities to spend part of their time demonstrating that due process does exist albeit not in the sense of the ordinary justice system, precisely because these are different legal systems. They have also had to explain that human rights are respected, that the authorities are prepared to hear and resolve llaki (conflicts) and that there is less risk of making mistakes since a llaki is not resolved through the individual decision of a judge but through a collective resolution of the community.

The peoples of Ecuador have to face diverse questions about Indigenous justice: from the fact that it does not respect due process to the fact that it is an expression of savagery. Photo: CONAIE

The peoples of Ecuador have to face diverse questions about Indigenous justice: from the fact that it does not respect due process to the fact that it is an expression of savagery. Photo: CONAIE

Declining of jurisdiction and judicial racism

As a coordination mechanism between the Indigenous and ordinary justice systems, the Organic Code of the Judiciary establishes the possibility of declining jurisdiction whereby Indigenous authorities may request that the ordinary judge respect the guarantee provided by the natural judge and refrain from dealing with an act committed in an Indigenous jurisdiction. However, in practice, the judges of the ordinary justice system ask for requirements beyond what is foreseen in the regulations: documented proof that the individual is Indigenous, proof that the case has already been tried by the Indigenous justice system and proof that they are the territorial authorities. There have consequently been few cases where jurisdiction has been declined in favour of the Indigenous justice system.

The ordinary judges have justified their refusals to decline jurisdiction with various arguments: that the ordinary judge was the first to hear the case; that they are more likely to correctly judge cases of domestic violence; that they are more likely to enforce international human rights standards; that the Indigenous authorities do not have legal status; that the appointment granted by a public institution has not been submitted; that the statute does not set out the jurisdictional power of said community; or that the cases were not previously resolved.

It is therefore the ordinary justice system that has the final say over what can and cannot be resolved by the Indigenous justice system. Racism is consequently replicated through subordination and submission to the ordinary justice system.

It is therefore the ordinary justice system that has the final say over what can and cannot be resolved by the Indigenous justice system.

As if this were not enough, the Organic Code of the Judicial Function also talks of the principle of Indigenous pro-jurisdiction, that is, in case of doubt, this justice system should always be preferred. In addition, the Organic Law of Jurisdictional Guarantees and Constitutional Control establishes that the Constitutional Court must respect the principle of autonomy: “The authorities of the Indigenous nationalities, peoples and communities shall enjoy a maximum of autonomy and a minimum of restrictions in the exercise of their jurisdictional functions, within their territorial sphere, in accordance with their own Indigenous law.”

They have nonetheless worn down the Indigenous authorities with refusals that force them to appeal decisions through the Provincial Courts of Justice or file extraordinary actions for protection before the Constitutional Court. It is therefore the ordinary justice system that has the final say over what can and cannot be resolved by the Indigenous justice system. Racism is consequently replicated through subordination and submission to the ordinary justice system.

And yet, while it is true that the Indigenous justice authorities have faced a number of difficulties, there have also been cases in which the judges of the ordinary jurisdiction have favorably declined jurisdiction. This has, however, sometimes resulted in their respective administrative and disciplinary bodies sanctioning them with dismissal from their positions. The logical consequence of this is a fear on the part of justice operators to act within the framework of the constitution.

Racism entrenched in society and in the Judiciary causes the ordinary justice system to disregard the resolutions of Indigenous authorities. Photo: Corte Nacional de Justicia de Ecuador

Racism entrenched in society and in the Judiciary causes the ordinary justice system to disregard the resolutions of Indigenous authorities. Photo: Corte Nacional de Justicia de Ecuador

The difficult road to intercultural justice

The right to administer Indigenous justice lies in the application of a different legal system, based on other principles, philosophies, worldviews, cultural codes and logics that understand the dynamics of Indigenous life. At the time of its application, however, it is confronted by Western hegemony and its epistemic violence, a result of the survival of a structural racism that has not yet been dismantled. Despite Ecuador’s self-declaration as a plurinational and intercultural country, in practice, we continue to live in a colonial state that has made few adjustments.

For its part, the Constitutional Court has contributed to Indigenous justice, to the rights of nature and to collective rights. It has built a body of case law that directs Ecuadorian society to respect Indigenous Peoples, their self-determination and autonomy. There is nevertheless still much to be done at the level of ordinary justice system operators and other State agencies.

Despite Ecuador’s self-declaration as a plurinational and intercultural country, in practice, we continue to live in a colonial state that has made few adjustments.

Despite Ecuador’s self-declaration as a plurinational and intercultural country, in practice, we continue to live in a colonial state that has made few adjustments.

Indigenous Peoples are therefore facing great challenges, including the task of building a plurinational and intercultural State. This requires a true re-founding of the political system and the elimination of the State’s colonial elements. A true epistemic revolution is needed, an exercise that demands the real participation of the peoples who, throughout history, have been largely absent.

The challenge remains to strengthen the executive, legislative and jurisdictional powers of the communal governments in order to achieve full and effective exercise of the right to self-determination. This will require building an epistemic, intercultural and egalitarian dialogue, against a backdrop of equality, reciprocity, integrality and complementarity. Now that the constitutional gains have been made, the next step is to dismantle the conditions of domination so that Ecuadorian society can understand that all existing legal systems are valid, that all contribute to guaranteeing access to justice and that all enable the preservation of a harmonious life.