The new Constitution will establish the guidelines for Chile for the next 50 years. The Indigenous constitutional assembly members are aware of this and are therefore promoting a more complex political debate, which includes political autonomy, territorial autonomy and the recognition of legal pluralism. The recognition of Indigenous peoples’ collective and individual rights will lead to a change in the nation’s way of conceiving the State and its development model.

The new Constitution will establish the guidelines for Chile for the next 50 years. The Indigenous constitutional assembly members are aware of this and are therefore promoting a more complex political debate, which includes political autonomy, territorial autonomy and the recognition of legal pluralism. The recognition of Indigenous peoples’ collective and individual rights will lead to a change in the nation’s way of conceiving the State and its development model.

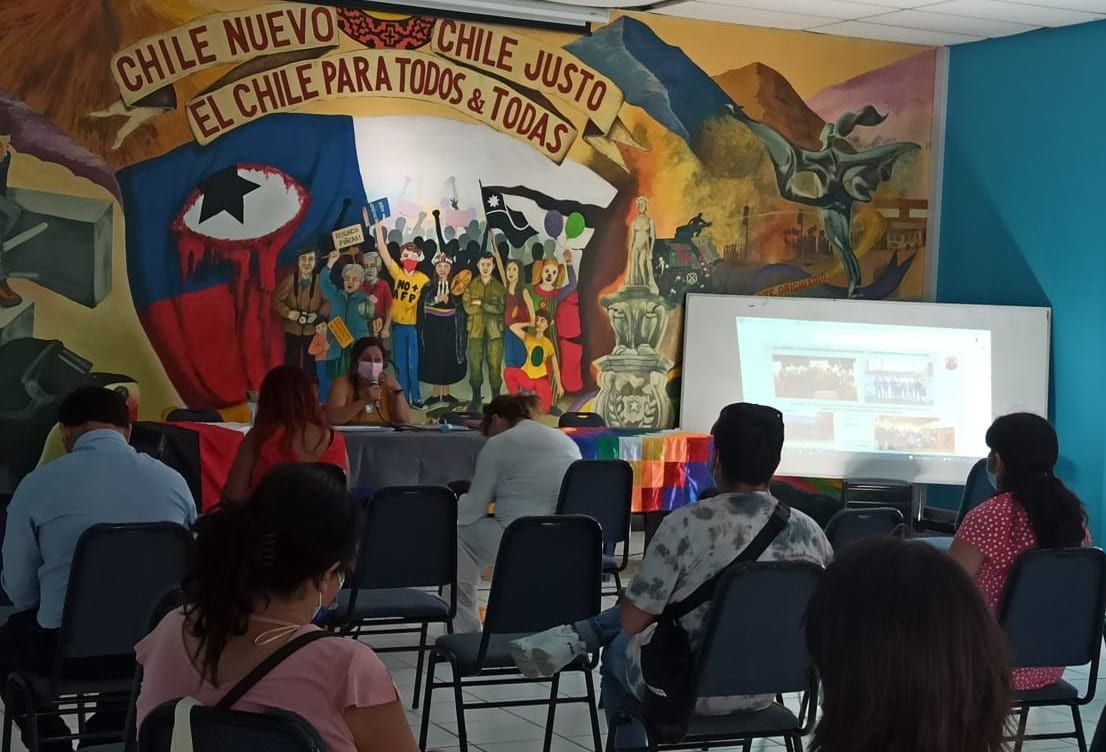

The Chilean constituent process has many virtues. On the one hand, its immediate source, the social outburst of 2019, detonated all pain accumulated for 40 years – the aftermath of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship and its constitutional system. The inequalities of the neoliberal model, exhausted and perfected by the Concertación governments, came to light. Among the thousands of marches and protests of the social revolt, several flags and causes were present: those of the feminist struggle, the claims of the Indigenous peoples, the LGTBQ+ flag, the rejection of the pension fund administrators and the demand for decentralization.

Over time and joining together with other appeals, a great demand emerged: that of a new constitution for Chile. This demand had an institutional channel, achieved through a transversal political agreement, which gave rise to the Constitutional Convention. This is how this body with gender parity (the first in history), which also has 17 seats reserved for Indigenous peoples, was configured as an escape valve for the political crisis that the country was experiencing.

The Indigenous peoples participate as collective subjects that put their demands, feelings and their own ways of building a new constitutional text on the table.

The Indigenous peoples put their demands, feelings and ways of building a new constitutional text on the table.

The inclusion of Indigenous peoples in the process was not an easy task. The constitutional reform that enabled this inclusion was the last link missing. This provision was only enacted a year after the October 2019 revolt, when Congress agreed and gave legislative form to the demand for participation. This milestone marks the path towards plurinationality: a path in which Indigenous peoples can participate as collective subjects that put their demands, sentiments and their own ways of building a new constitutional text on the table.

This is why Indigenous peoples have played a leading role since the beginning of the Constitutional Convention. While the Mapuche constitutional assembly member Elisa Loncon gained notoriety for being president of the Convention during the first six months of work, the rest of the reserved seats have brought other ways of doing politics to the commissions – both transitory and permanent. Unlike traditional politics, Indigenous politics is based on direct confrontation and on the demands of peoples and territories. This way of doing politics is far removed from the courtly halls, where differences tend to disappear in the so-called “democracy of agreements”.

The president of the Convention, María Elisa Quinteros Cáceres, and the Indigenous constitutional assembly member Wilfredo Bacian in a symbolic ceremony of initiation and support to the Indigenous Consultation of the Quechua People in the town of Mamiña. Photo: Quinteros Cáceres Press Office

Symbolic ceremony of the Quechua people in support of the Indigenous Consultation. Photo: Quinteros Cáceres Press

Construction from a native perspective

In order to analyze the contributions of Indigenous peoples in the constituent debate, we have to consider that there are 17 reserved seats representing 10 peoples. Of this total, the Mapuche people have a majority participation with seven seats, the Aymara people two seats, and the other eight peoples have only one seat each. Beyond the fact that each people has its own way of relating to power or of doing politics, no convention differs in the general guidelines, which are: plurinationality, political autonomy, territorial autonomy and recognition of legal pluralism. The main differences refer to the way in which each one, individually or as a bloc, is able to articulate their wills.

It is remarkable the way in which a common discourse regarding “buen vivir” (loosely translated to “good living”) and the rights of nature has been built. Each of the Indigenous seats has been able to describe and explain the way in which their peoples relate to Mother Nature through a harmonious and respectful relationship. These central elements in Indigenous peoples’ way of life has materialized into initiatives, debates and ideas that form the basis of constitutional proposals.

Never in 200 years of republican history has there been a democratic space where Indigenous peoples could participate on an apparent base of equal conditions.

The contributions of the reserved seats are significant to the constitutional debate and transcend the demands of the peoples.

In this way, it is evident that the contributions of the reserved seats are significant for the constitutional debate and transcend the demands of the peoples: they are relevant for the whole country. Never in 200 years of republican history has there been a democratic space where Indigenous peoples could participate on an apparent base of equal conditions and show their ways of relating to each other, their territorial realities, their worldviews and their particularities in a society increasingly homogenized by capitalism.

This participation and contribution is not merely decorative or folkloric. If we review the constitutional discussions, we will be able to appreciate that the proposals of the constitutional assembly members and the Indigenous popular participation propose a new way of conceiving the rule of law. They are committed to plurinationality in the political sphere, autonomy in the territorial sphere, the right to collective ownership of land and water, the rights of nature as the new axis of the economic model, and cultural rights as a proposed constitutional principle. It is here that we move on to the complexities and dangers.

The constituent of the Colla people, Isabel Godoy Monardez, promotes the recognition of the plurinational and intercultural condition in Chile, and territorial, cultural, political and linguistic rights. Photo: Godoy Monarde Press

The constituent of the Colla people, Isabel Godoy Monardez, promotes plurinationality and interculturality. Photo: Godoy Monarde

The difficulty of interpreting plurinationality

The way in which Indigenous peoples have made themselves felt and heard through their languages, their colors, their feelings and their sufferings has materialized into basic proposals for the recognition of their rights. It is the first time that the demands of the Indigenous peoples resound in a space of political relevance. In this new context, the rest of the forces have found it difficult not to empathize with the peoples and in many cases to oppose (at least publicly) the demands that have been raised, individually or collectively.

It is undeniable that the claim of plurinationality is installed and that no one within the great majorities of the Convention would be able to deny that Chile will be plurinational. However, a relevant problem is the different interpretations of the concept of “plurinationality”. Chile is the only country in the region that does not constitutionally recognize Indigenous peoples: the only legal instruments that recognize Indigenous rights within the country are the ILO Convention 169 and the Indigenous Law No. 19,253.

The Constitutional Convention is under constant attack of communication. The same occurs with the demands of Indigenous peoples.

The Constitutional Convention is under constant attack of communication. The same occurs with the demands of Indigenous peoples.

On the other hand, the constitutional model of the dictatorship is highly concentrated in the political, territorial and economic spheres. For this reason, the demands for self-determination are often not understood in their full dimension. In fact, the very same members of the Constitutional Assembly confuse self-determination with a mechanism of differentiation between first- and second-class Chileans, as if the Indigenous peoples were a new elite. Nothing could be further from the truth. The Indigenous peoples are simply asserting rights that are already recognized by international law, accepted by the country and that imply a limit to the actions of the Constitutional Assembly.

Another complexity arises in the public debate, where things aren’t easy either. The Constitutional Convention is under constant attacks of communication, and the same occurs with the demands of the Indigenous peoples. To this, we must add the prevailing ignorance about the reality of Indigenous peoples and about the respective concepts in general. Some referred to the demand for plurinationality as a masked harakiri to the State, while others labeled the convention as “extremist”. In addition, others maliciously contrasted the Indigenous legal systems with the current judicial system, which they consider to be more evolved, modern and preferable.

Many non-Indigenous constitutional assembly members also support the principles of plurinationality, legal pluralism, interculturality and territorial autonomies. Photo: Stingo Camus Press

Non-Indigenous constituentional assembly members also support plurinationality and territorial autonomies. Photo: Stingo Camus Press

The challenge of facing a historic opportunity

In a high-level debate, the respect for human rights and a new form of collective, plural and harmonious relationship between the nations that coexist in the same State should prevail. The profound recognition of the collective and individual rights of Indigenous peoples will lead us to a significant change in the way of conceiving the Chilean State and its model of development. The new Constitution should not only establish a concept of plurinationality, but should also provide elements that will allow us to continue advancing towards greater spaces of participation and development; and due autonomy, within the framework of nations that seek a common destiny, in harmony and peace.

We are facing a historic opportunity in which our generation can translate the rights that have been denied to us for centuries into a new Constitution: the right to actively participate in the political life of the country, to have our own development in harmony with Mother Earth and to stop being seen as people who commit illegalities and crimes of all kinds. It is an opportunity for the Chilean people to begin to be perceived as practitioners of their own rights, according to the conceptions of what is just according to our original cosmovision.

In any case, the Chilean constitutional assembly, avant-garde in its configuration, is playing at a transcendental issue: the recognition of the peoples, of their rights and of the State as a collective, multiple, diverse and complex political subject. In the hands of the 154 constitutional assembly members lies the formula to achieve these objectives or, at least, to get closer to them in the Chile of the next 50 years.

Juan Carlos Cayo Rivera is Aymara and a lawyer from University of Tarapacá. He also has a Master’s Degree in Constitutional Law and is a candidate for a Doctorate in Law from the University of Seville. He is currently an advisor to the Colla people’s constitutional assembly member, Isabel Godoy Monardez. Contact: juacayriv@alumn.us.es and juancarloscayorivera@gmail.com