The people of the Peruvian Amazon have the goal of building an autonomous and intercultural justice system that reincorporates customary law and the dialogued sanctions applied by the wise men and elders. To this end, the Awajún Autonomous Territorial Government is trying to limit monetary reparations and the deprivation of liberty in prison cells that are not prepared for prolonged stays. The challenge lies with the members of the community to rely on their justice system and to stop resorting to the ordinary justice of the State.

The people of the Peruvian Amazon have the goal of building an autonomous and intercultural justice system that reincorporates customary law and the dialogued sanctions applied by the wise men and elders. To this end, the Awajún Autonomous Territorial Government is trying to limit monetary reparations and the deprivation of liberty in prison cells that are not prepared for prolonged stays. The challenge lies with the members of the community to rely on their justice system and to stop resorting to the ordinary justice of the State.

Located in the northwestern Amazonian region of Peru, the Awajún people have a population of approximately 70,000 inhabitants, divided into 488 communities. As they developed their social life, the Awajún established their own legal system and their own forms of law production. Thus, they shaped their own patterns of justice in the same way as did other societies and cultures around the world. In the evolution of social control, three phases can be identified: primordial social control, the era of prison cells and the era of territorial justice.

The Awajún Autonomous Territorial Government faces the challenge of building a community, autonomous and intercultural justice system. Photo: Alejandro Parellada

The Awajún Autonomous Territorial Government faces the challenge of building a community, autonomous and intercultural justice system. Photo: Alejandro Parellada

Doctrines of the sages and elders

Early social control was marked by the rigid precept of "an eye for an eye". Although it was collectively agreed upon, its implementation depended on each aggrieved person. In this primitive justice, the Awajún practiced the doctrines of wise men and elders who sowed a culture of social coexistence in the collective knowledge as a discipline of life. Conflicts were not resolved according to the law of the strongest (as some positivist theories maintain), but penalties were applied to avoid major conflicts.

In other words, Awajún justice was based on the practice of self-tutelage, but social peace was actually sustained under the leadership and control of the elders who prevented any unilateral act of justice. An act of justice outside the collectively established canons was not considered justice. For this reason, when any family endorsed cruelties inflicted by its members, it was remedied in accordance with the sentence determined by the elders.

Capital punishment as the maximum punishment was applied to a situation that, under the observance of the elders, became insurmountable in any other way. Homicide and adultery were considered very serious cases, whose solution ended with the death sentence of the offenders. This culture of justice only began to be replaced in the 1970s under the influence of the State and the protection of fundamental rights. To a large extent, it was also influenced by the gospel and schooling.

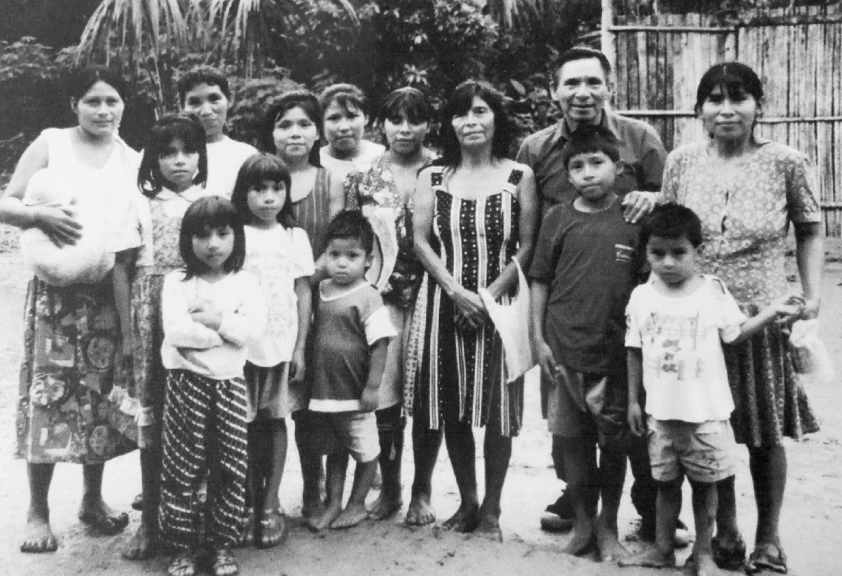

In the past, Awajún justice was based on self-tutelage, dialogue and leadership of the elders. Photo: Dati Family Archive

In the past, Awajún justice was based on self-tutelage, dialogue and leadership of the elders. Photo: Dati Family Archive

Deprivation of liberty

The second phase is known as the era of the prison cells. This form of punishment does not resolve conflicts, but rather aggravates them, and also perverts Awajún justice. This phenomenon developed as a consequence of a complex legal relationship that the State imposed on the Indigenous Peoples after the legal recognition and granting of legal personality to the so-called native communities in 1974.

Minor offenses that in the past were solved with customary rules and purges with corrective plants, are now punished with temporary deprivation of liberty in prison cells. To this end, each community is forced to build its own places of deprivation of liberty. Depending on the seriousness of the offense, the penalty is, at most, one week of confinement. This method of punishment was applied for minor offenses and, on rare occasions, for serious crimes such as adultery.

In their attempt to impose penalties for serious and very serious crimes, some Awajún territorial sectors have established, since 1980, a sort of higher instance of justice. Although attempts have been made to resolve homicides, solutions have been limited to civil reparations. So far, there is no consensus on the type of penalty to be established. Therefore, this practice does not contribute to the consolidation of community justice and leaves an open space for the imposition of ordinary justice.

The adoption of sanctions based on prolonged confinement goes against Awajún culture and undermines community justice. Photo: Alejandro Parellada

The adoption of sanctions based on prolonged confinement goes against Awajún culture and undermines community justice. Photo: Alejandro Parellada

Justice today

This last phase could be called territorial justice since it takes up the experience that precedes it and tries to institute Awajún justice through a code specific to the new Awajún Autonomous Territorial Government (GTAA). At this stage, an attempt is being made to change civil reparations for another form of sanction that only includes penalties. The objective is to prevent money from being mixed with punishment, as is currently the case. The monetization of punishment is perverting the execution of justice.

In this way, it is intended that minor, serious and very serious crimes be resolved autonomously, for which it is necessary to create mechanisms of social control through its own justice system. The higher instance of justice has been created with the purpose of resolving crimes without resorting to the ordinary justice system, in fact, many cases have been resolved more quickly. However, in its 48 years of institutional life, it has not been able to consolidate itself as a system of its own with the capacity to maintain its autonomy, nor has it projected its image to the community as a strong institution.

On the other hand, sentences have been increased, but the cells, built for punishments that lasted hours or at most days, do not meet the minimum conditions of living for a person to be encarcerated for period of months, as now established by the highest instance of justice. Moreover, the judges lack training in common law and have little knowledge of the fundamental rights essential to understanding the national legal system. With little knowledge of the Constitution, jurisprudence, international human rights treaties, and criminal and civil law codes, local justice operators are unable to strengthen their trial skills.

It is intended that minor, serious and very serious crimes be resolved autonomously, for which it is necessary to create social control mechanisms through its own justice system.

The highest instance of justice has been created with the purpose of solving crimes without resorting to the ordinary justice system.

These limitations are compounded by the absence of customary institutions that help strengthen procedural canons. Nor has a proper procedure been developed to guarantee a fundamental right such as due process. These aspects have been weakening the autonomous institutionality of the Awajún justice system and have contributed to the fact that the ordinary justice system has been taking away its powers: more and more crimes, especially violations against minors and child pensions, are being channeled through the ordinary justice system, at the request of the aggrieved parties themselves.

Although no binding jurisprudence has been established, the Constitutional Court's Decision 07009-2013-PHC has initiated a path that leads to the removal of the communal authorities' powers of judgment: "In the scenario described, it is clear that for example, all those crimes that affect fundamental rights such as life, health, physical, psychological and moral integrity, freedom, among others, or that may affect in any way the interests of those persons located in special and/or sensitive condition such as children, adolescents, pregnant women, the elderly, etc., could not be subject to knowledge in the scope of communal justice."

In their search for autonomous and communitarian justice, the Awajún people seek to dismantle punishments based on confinement and monetary reparations. Photo: Alejandro Parellada

In their search for autonomous and communitarian justice, the Awajún people seek to dismantle punishments based on confinement and monetary reparations. Photo: Alejandro Parellada

Community justice as part of the exercise of autonomy

The challenges faced by the highest instance of justice are a consequence of a weak communal justice process that has contributed to the fact that the members of the community themselves undermine it by resorting to the ordinary justice system. Added to this is the State's lack of interest in strengthening community justice.

The Awajún people include community justice as one of the pillars of the exercise of autonomy: it is not possible to govern autonomously if some factor of autonomy, which lies precisely in the exercise of social control, does not function under community determination. Nor should the development of autonomy be confused as an absolute attribution given that, whether we like it or not, we are under the constitutional protection of human rights.

Although this can be misinterpreted as a submission to state rules to the detriment of customary matters, what the Awajún people propose is to build a community justice system that, in compliance with the constitutional order, applies a customary law that is satisfactory for the local community and respectful of established human rights standards. Otherwise, it will not be possible to meet the collective expectations of community justice.

The Awajún people include community justice as one of the pillars of the exercise of autonomy.

The Awajún people include community justice as one of the pillars of the exercise of autonomy.

In this third phase, we intend to establish community justice through a territorial vision of the subject "people" and relaunch the major justice instance in the 23 territorial sectors that make up the Awajún Autonomous Territorial Government. In this sense, it is necessary to remedy the following aspects:

– Strengthen communal justice as the first instance of territorial autonomous justice.

– Strengthen the territorial vision of justice with the establishment of 23 higher instance courts, which will fulfill the role of second instance of community justice.

– Train first and second instance judges in constitutional and human rights issues.

– Collectively establish a Community Justice Code.

– Propose to the State the establishment of a Special Protocol to establish terms of coordination with the ordinary justice system.

– Establish penalties that are distinguishable from civil reparations to curb the monetization of penalties.

– Solve 100% of crimes through community justice for the exercise of autonomy.

– To serve sentences within the Awajún territory.

It must be taken into account that non-Indigenous people also live in the Awajún territory. Therefore, if it is a matter of applying community justice, the social control system must include them. In this framework, the Awajún people must involve them and include them in the dialogues to build community and intercultural justice, which is the greatest challenge that awaits us in the next five years.