As part of the process of Japan’s transformation into a powerful imperial state in the 19th century, Japanese academia tried to portray the Ainu as inferior to the Japanese. Human remains from the Ainu, as well as other Indigenous Peoples and ethnic minorities, were used to substantiate this claim. After years of struggle and legal claims, some of the ancestral remains from desecrated graves began to be returned to their communities.

Japan is generally referred to as a homogenous society that puts great worth on traditional values and practices. This narrative, however, omits the fact that the Japanese population is culturally and ethnically diverse. The population includes: the Ainu who were recently recognized as an Indigenous people of Japan and who mostly reside in Hokkaido and Ryukyuans – people Indigenous to Okinawa and other islands of the Ryukyu archipelago, but who are not recognized as such by the government; the Zainichi – Koreans born and raised in Japan; foreign migrants; naturalized immigrants; and the Burakumin, an outcast social group forcibly placed at the lowest level of the traditional Japanese feudal order who continuously struggle for a socially equal position in the modern Japanese society.

These groups form a vital part of Japanese society, though their cultures and struggles are not generally known to the public. Reasons for this vary on a case-by-case basis, but discrimination is widely recognized as one of them, as well as the lack of recognition of their social status by the Japanese State. This historic and structural discrimination against Indigenous Peoples and ethnic minorities of Japan has created an environment where ancestral graves could be desecrated by academics and where the return of stolen ancestors and ancestral remains could only be possible after years of campaigning by Indigenous leaders.

The Ainu were recently recognized by the government of Japan as an indigenous people. Traditional Ainu house. Photo: Kanako Uzawa

The Ainu were recently recognized by the government of Japan as an indigenous people. Traditional Ainu house. Photo: Kanako Uzawa

The Ainu of Japan

It was only in 2019 that the Ainu were recognized as an Indigenous people of Japan in Japanese legislation, even though the Ainu people have continued carrying their traditional livelihoods of hunting, fishing, and foraging wild plants, and kept some of their cultural practices alive to the present day.

The Ainu have traditionally resided in Hokkaido, parts of northern Honshu, the Kuril Islands, and southern Sakhalin (the latter two of which are currently part of today’s Russia). Over the years disputes over these latter two areas have taken place between the Ainu and the Wajin (non-Ainu or the ethnic Japanese), as well as between Japan and Russia. The distinct Ainu language, which differs from the Japanese language, has fascinated many researchers across the globe. Today it is believed that there are no native speakers of the Ainu language left in Japan.

This lack of disaggregated data helps to not only perpetuate the myth that Japan is ethnically homogenous, but also hides the differences in the social and economic status of different ethnic groups.

This lack of disaggregated data not only perpetuate the myth of ethnically homogenous Japan, but it also hides the differences in the social and economic status of different ethnic groups.

The ethnic make-up of Japan is unclear since the country does not conduct its national census on the basis of ethnicity, thus it’s difficult to ascertain the true number of Ainu in today’s Japan. This lack of disaggregated data helps to not only perpetuate the myth that Japan is ethnically homogenous, but it also hides the differences in the social and economic status of different ethnic groups. However, the Hokkaido Ainu Living Conditions Survey conducted by the Department of Hokkaido Environment and Lifestyle in 2017 shows the population of the Ainu in Hokkaido as 13,118 individuals. When considering this number, one should be aware of the vast difference between the 2017 survey and the one conducted in 2006 which shows 23,782 individuals, as it suggests a 45% decline in the number of the Ainu population.

One could assume that the difference in the number can be at least partially linked to discrimination and lingering prejudices. In addition to the Ainu population in Hokkaido, there are many Ainu who move to urban cities in southern Japan for greater opportunities in education and employment, although the number of Ainu who live outside Hokkaido is not known. In addition to Ainu who live in today’s Japan, according to the All-Russia Population Census 2010, there were 109 individuals in Russia who identified themselves as Ainu.

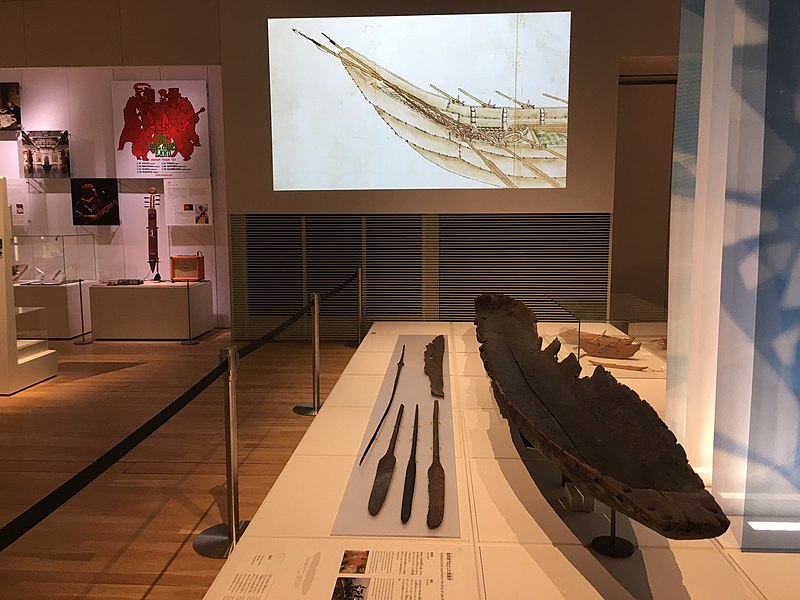

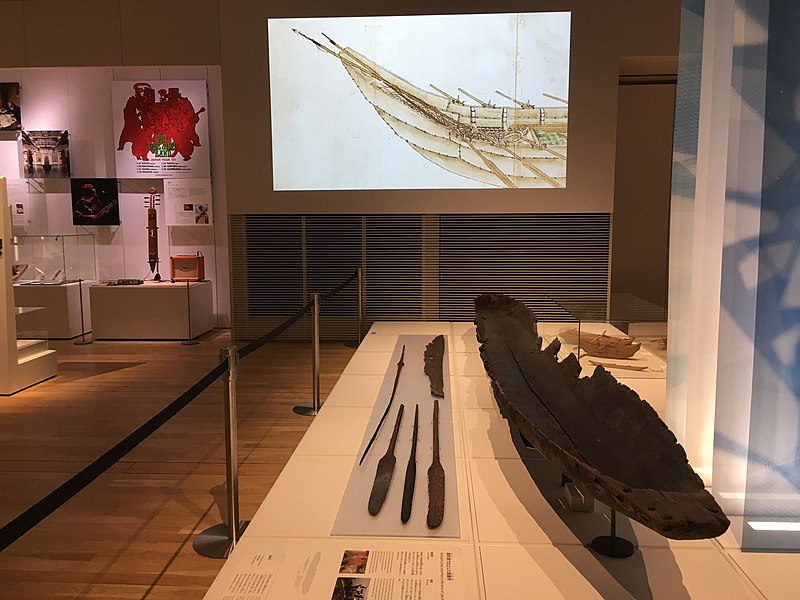

It is difficult to determine the number of Ainu living in the country.National Ainu Museum: Photo: Wikipedia

It is difficult to determine the number of Ainu living in the country.National Ainu Museum: Photo: Wikipedia

A belated recognition

It is only recently that the word Indigenous or the concept of Indigenous Peoples gained recognition in Japan and two important factors contributed to that. Firstly, the influence of the global Indigenous movement played a huge part in raising awareness. Indigenous Peoples’ rights activists, though a variety of global platforms, joined forces and networked across the globe. They met at meetings of the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations and the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and through processes, such as the years of work on the United Nation Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, passed in 2007.

Increased Ainu participation at UN meetings since 1987, which was the first attendance of the Hokkaido Ainu Association at the UN following Prime Minister Nakasone´s statement of Japan being a mono-ethnic nation in 1986, raised awareness of what it means to be Indigenous in Japan. This was followed by grassroots-based activities that encouraged Ainu and Ryukyuan youth to attend meetings and hold seminars with activists and their home communities in Japan.

It is only recently that the word Indigenous or the concept of Indigenous Peoples gained recognition in Japan. The influence of the global Indigenous movement played a huge part in raising awareness.

It is only recently that the concept of Indigenous Peoples gained recognition in Japan.

Secondly, the case of the Nibutani Dam in 1997, the construction of which destroyed cultural sites and traditional cultural practices of Ainu as well as biodiversity of the surroundings in the community, also raised awareness of Indigenous people in Japan.

Two local plaintiffs stood up in court against the construction of the dam, and for the first time in the country’s history, the Sapporo District Court recognized the Ainu´s individual right under Article 13 of the Japanese Constitution, as well as rights to enjoy their own minority culture under Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This resulted in stirring up public awareness of the Ainu as Indigenous people and thus, Ainu people began to take a strong step forward in the public discourse as themselves being Indigenous to the land of Hokkaido.

Researcher and artist Kanako Uzawa promotes Ainu culture. Photo: Dan Mariner for Tempura Magazine

Researcher and artist Kanako Uzawa promotes Ainu culture. Photo: Dan Mariner for Tempura Magazine

Academic colonialism and repatriation activism

When Japan opened the country to the West with the Meiji Restoration (1868), theories of race and the new science of evolution from Europe and the Americas took root among Japanese academia. Japan’s successful annexation of Hokkaido in the late 19th century set the scene for Japan to be seen as one of the powerful colonial states in the world. Thus, in addition to the academic practices of Japan, it became important for Japan’s imperialist project that Japan show the Ainu as being inferior to the Japanese. Physical anthropology research, with this objective in mind, came to be conducted at the time and continued as late as the mid-1960s.

With the annexation of Hokkaido, Ainu people became easily accessible and were seen as fascinating research specimens. Under the influence of Social Darwinism and racial discourse from the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries, the theory of Ainu being Caucasian cousins attracted many scientists both in and outside of Japan. This resulted in a large collection of Ainu skeletons, funeral accessories and human remains being stolen and scientifically researched. In fact, over 1,500 skeletons were stolen and stored in Japanese universities, although some were later repatriated to their home communities.

As a result of the repatriation activism, today the human remains of 1,323 individuals and 287 boxes of aggregated remains have been moved and housed in the Upopoy National Ainu Museum.

Today the human remains of 1,323 individuals and 287 boxes of aggregated remains have been moved and housed in the Upopoy National Ainu Museum.

In 2008, Ainu elder Mr. Ryukichi Ogawa discovered that a huge number of Ainu ancestral remains had never been disclosed by Hokkaido University. His immediate action and effort to repatriate these Ainu human remains drew both community and media attention. This has led to a series of repatriation litigations, as well as triggered a discussion of Ainu human remains in Japan.

It also brought up a huge amount of debate and discussion among Ainu communities on the issue of repatriation of their human remains. It also led the government’s Ministry of Education to lead an investigation into Ainu human remains housed in museums and universities in Japan. As a result of this repatriation activism, today the human remains of 1,323 individuals and 287 boxes of aggregated remains have been moved and housed in the Upopoy National Ainu Museum where they await identification for their return to their appropriate communities. Opened in 2020, Upopoy museum was specifically designed by the government of Japan as the main center for promotion of Ainu culture and acts as a temporary resting place for Ainu ancestral remains retrieved from academic institutions and museums.

Upopoy museum was designed by the government of Japan as the main center for promotion of Ainu culture and acts as a temporary resting place for Ainu ancestral remains. Photo: Wikipedia

Upopoy museum was designed by the government of Japan as the main center for promotion of Ainu culture and acts as a temporary resting place for Ainu ancestral remains. Photo: Wikipedia

Re-evaluating Japan’s history

Meanwhile, repatriation activism in the form of demands for an apology from the universities and for the speedy return of the remains, now including those of Ryukyuan ancestors, continues.

Grave robberies by scholars are now recognized as academic colonialism and until now continue to have devastating impacts on the Ainu community and people’s memory. Debates around repatriation of ancestral remains serve as a reminder of that dark period in the history of Ainu people that invites us to re-evaluate the colonial history of Japan and the stories behind the history.

Kanako Uzawa is an Ainu scholar, advocate, and artist. For more information about Dr. Uzawa and her work please visit her page: https://ainutoday.com/