The Aché people inhabited the vast eastern jungles of Paraguay for centuries. Their history is marked by bloodshed and dispossession. Kryýgi's life did not escape this dynamic: after her family was murdered, her name was changed to Damiana, she was forced to work as a maid and then was taken to Argentina. When she reached adolescence, she was admitted to a neuropsychiatric hospital where she died of tuberculosis. The condition of her remains was not the best. While her skeleton was lost in the La Plata Museum, her skull ended up in a German university. A century later, the Aché people managed to reconstruct her body and return it to the jungle from where it should never have left.

The Aché people inhabited the vast eastern jungles of Paraguay for centuries. Their history is marked by bloodshed and dispossession. Kryýgi's life did not escape this dynamic: after her family was murdered, her name was changed to Damiana, she was forced to work as a maid and then was taken to Argentina. When she reached adolescence, she was admitted to a neuropsychiatric hospital where she died of tuberculosis. The condition of her remains was not the best. While her skeleton was lost in the La Plata Museum, her skull ended up in a German university. A century later, the Aché people managed to reconstruct her body and return it to the jungle from where it should never have left.

“The life of the dead endures in the memory of the living.”

Cicero

“The life of the dead endures in the memory of the living.”

Cicero

Since the Spanish invasion of the region during the first half of the 16th century, there have been accounts of persecutions, manhunts and kidnappings of children who were placed into servitude or became subjects of scientific experimentation. This practice became very common between the 1950s and 1970s, when the dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner (1954-1989) applied the martial order of compulsory sedentarization in the name of progress. The direct consequence of this measure was the so-called Aché genocide.

On the evening of 11 June 2010, the skeleton of a headless girl and the skull of an adult arrived in the community of Ypetĩmi (205 kilometers from the capital Asunción) from the Museo de la Plata in Argentina, a century after they were kidnapped. After a profoundly moving ceremony, a small group carried the remains for their proper burial in the mountains of their ancient ekõandy (territory of existence and experience).

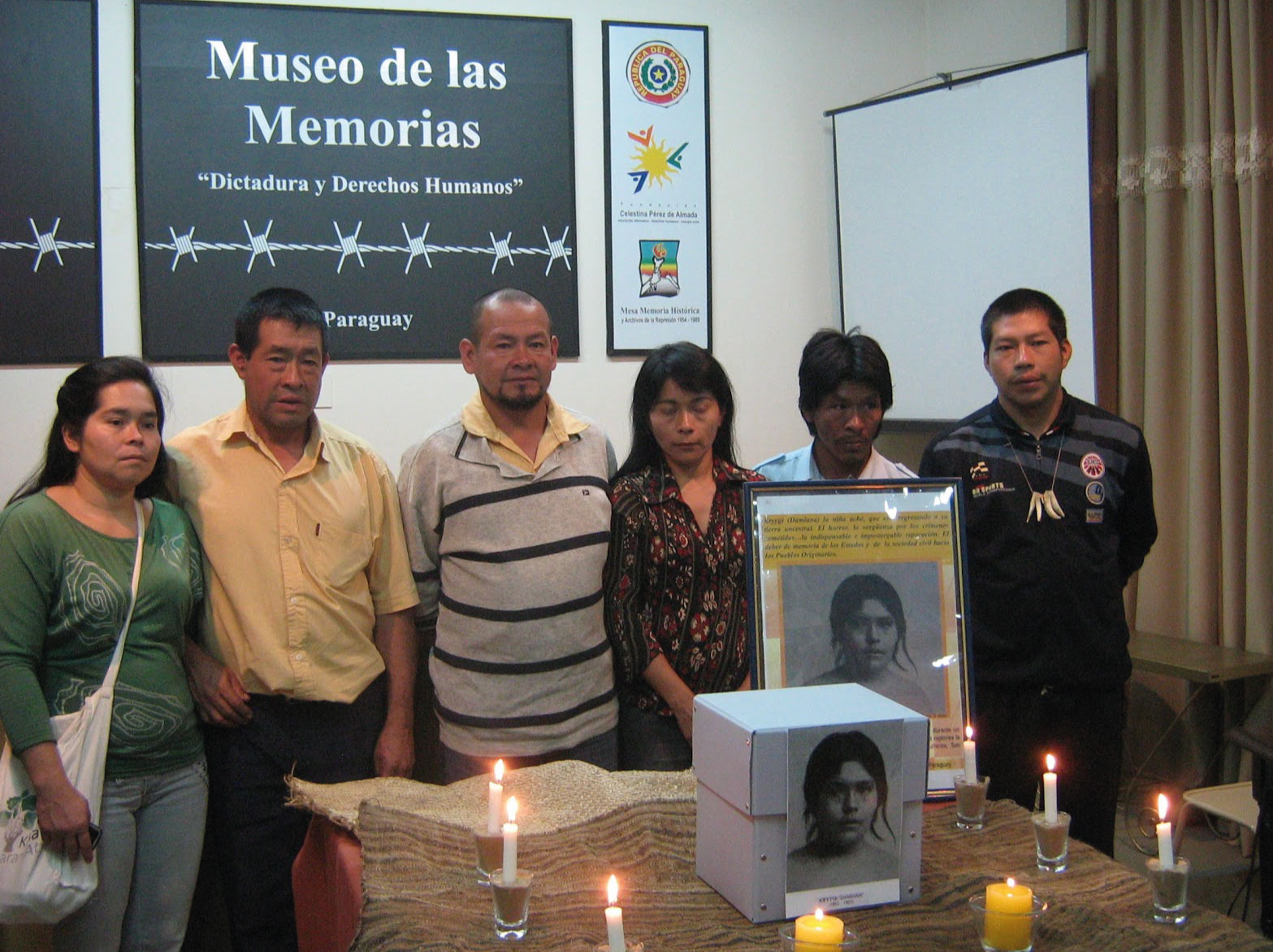

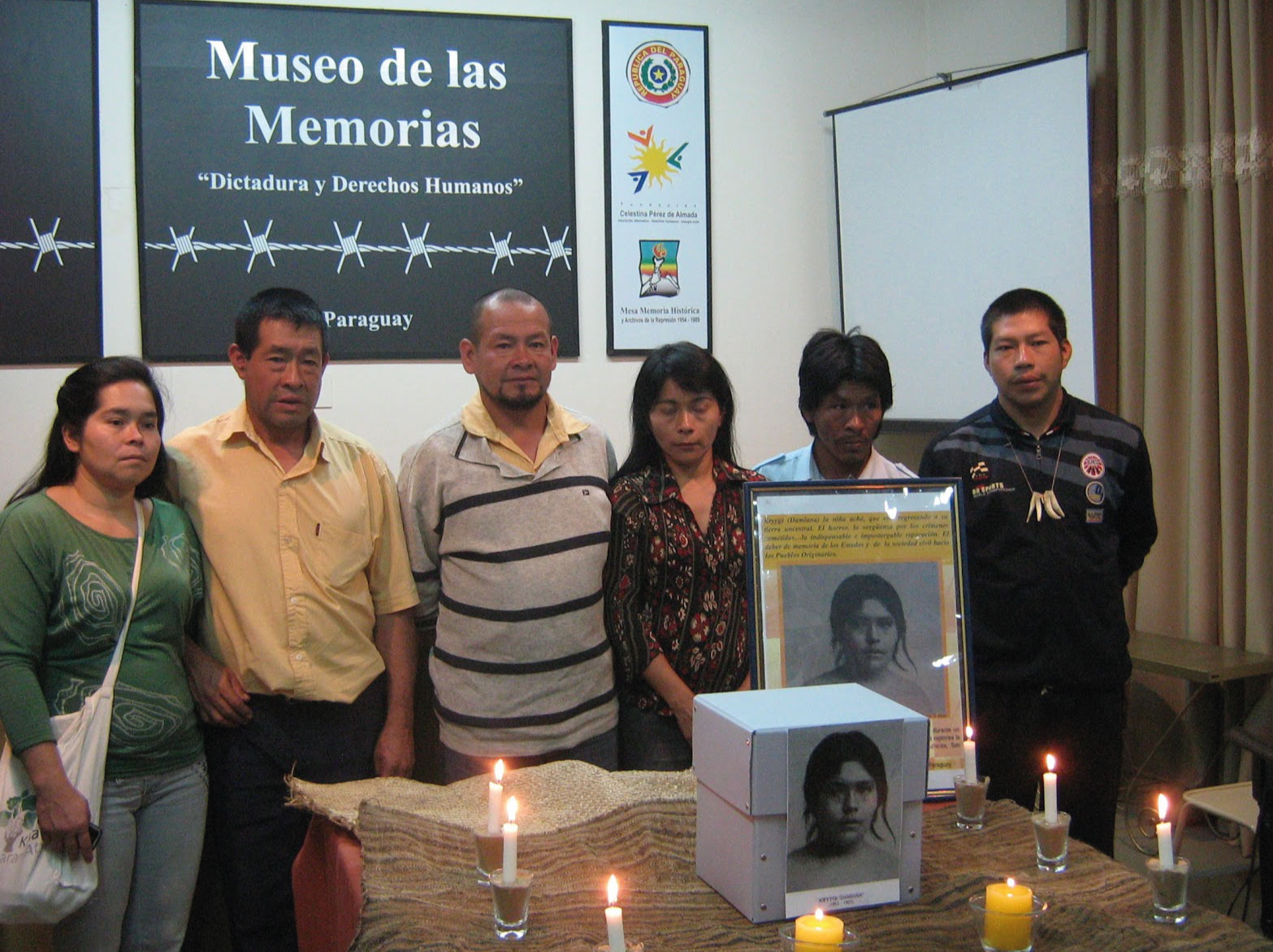

Finally, in May 2012, the skull belonging to the skeleton of the girl was returned from the Charité Hospital in Berlin. Now with the skeleton intact, the girl was identified by the present-day Aché as a ryýgi (bush armadillo). The other skeleton, belonging to an Aché farmhand who worked in the Taba'i yerba mate fields and was killed with an axe to the head, is still waiting to recover his ancestral identity.

Photographs and remains of Kryýgi during the restitution ceremony. Photo: Infojus

Photographs and remains of Kryýgi during the restitution ceremony. Photo: Herman ten Kate y Charles de la Hitte

The beginning of the tragedy

In September 1896, in the region of Villa Encarnación (present-day department of Itapúa), a group of settlers ambushed an Aché family gathered around a campfire in the bush. They accused them of having killed a horse. In the scuffle they killed a mother of a girl who was between the ages of three and four. The girl, who was unharmed, was taken into servitude to a ranch, where she was baptized as Damiana: the name of the saint who is celebrated on 27 September, which was the day her family was murdered.

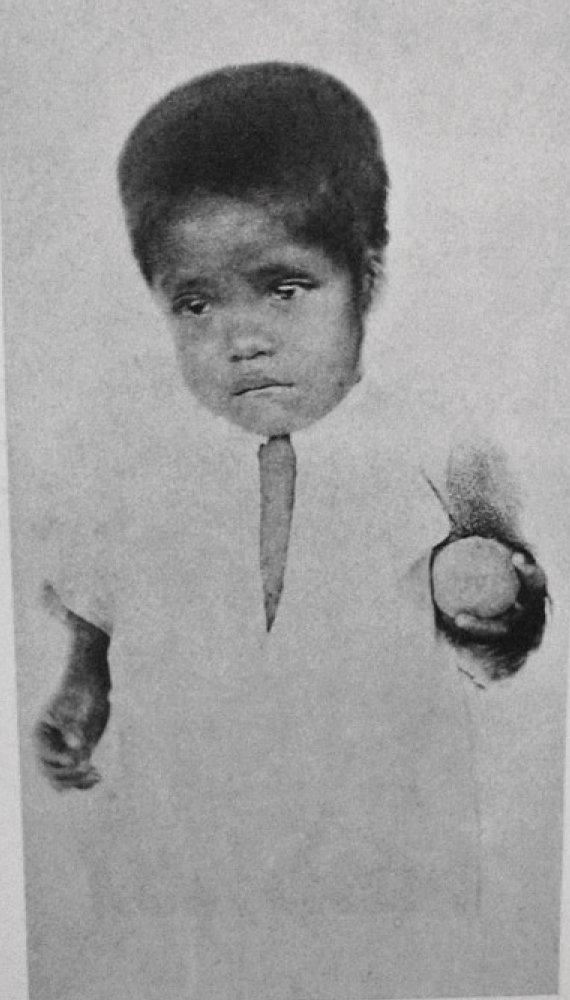

That same year, the remains of what was thought to be her mother were recovered in situ by the Dutchman Herman ten Kate and the Frenchman Charles de la Hitte, the head and assistant of the Anthropological Section of the Museum of La Plata. Both were also able to make the first observations, measurements and photographs of the girl, noting her sorrowful state.

In 1898, through the intermediation of De la Hitte, the girl was taken from Paraguay to the town of San Vicente, in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, as a servant for the Korn family who were of German origin. When she reached adolescence in 1907, she was committed to a psychiatric hospital run by the physician Alejandro Korn, who considered that her sexual behavior, free and unrestrained, should be punished and rectified. The neuropsychiatric hospital was located near the city of La Plata, in the town of Melchor Romero. It was there that the then-head of the Anthropological Section of the Museum of La Plata, Roberto Lehmann-Nitsche, also German, conducted studies, undressed her and took the photographs that would become the last and valuable records of her existence.

The skull and brain were sent to the Anthropological Society of Berlin “for special study” on behalf of Professor Hans Virchow, who received them in January 1908, thanking them for what he considered a “wonderful gift.”

The skull and brain were sent to Berlin “for special study” for Professor Hans Virchow, who considered them a “wonderful gift”.

In 1907, Kryýgi died of tuberculosis, overwhelmed by loneliness in an unknown world that she entered violently and against her will. Her body was abused in the name of science, autopsied, measured and decapitated. Her trunk and limbs remained in La Plata. Her skull and brain were sent by Lehmann-Nitsche to the Anthropological Society of Berlin "for special study" on behalf of Professor Hans Virchow, who received them in January 1908, thanking them for what he considered a "wonderful gift". However, the fate of her organs remains unknown.

It was not until 1913 that Lehmann-Nitsche added the headless skeleton of Kryýgi to the Museo de La Plata collection, permanently removing it from his private study collection. The hair and skin were poorly registered in the collection and were not found and identified at the Museo de La Plata until 2016. Their restitution is still pending. The skull was incorporated into the Institute of Anatomy of the Berlin Medical School, two years after it was received, dissected, and studied.

Ceremony of restitution of the Kryýgi skull at the Museum of Memories in Asunción in 2012. Photo: Colectivo Guias

Ceremony of restitution of the Kryýgi skull at the Museum of Memories in Asunción in 2012. Photo: Colectivo Guias

The long road to restitution

In March 2007, the Native League for Autonomy, Justice and Ethics (Linaje), made up of members of the Aché Kuētuvyve community (now disappeared), made a formal claim for the restitution of the remains of their relatives to the Museum of La Plata. At the end of that year, Emiliano Mbejyvági traveled as an Aché emissary to La Plata to expand the request, asking for the restitution of the bodies of Kryýgi and other members of his people deposited there. The request also included the objects taken from the massacre site, offering in exchange Aché items of daily use.

The Honorable Academic Council of the National University of La Plata constituted a large ad hoc commission to follow up and respond to the request. To this end, they took into account Law N o . 25.517 and its regulations, which stipulate that the remains of Indigenous people that are part of museums or public and private collections can be made available to the peoples who claim them. However, it was only in 2009 that the Aché Native Federation of Paraguay (FENAP) obtained its legal status, was legitimized before the Paraguayan State as representative of the Aché people and was able to continue with the claim.

Law No. 25.517 and its regulations stipulate that the remains of Indigenous people that are part of museums or public and private collections may be made available to the peoples of belonging who claim them.

Law No. 25.517 stipulates that the remains of Indigenous people in museums may be made available to the people to whom they belong.

On 18 December 2009, the Academic Council issued Resolution N o . 283 approving the restitution of part of Kryýgi's remains and the farmhand’s skull. The latter had been donated to the La Plata Museum in August 1904 by the then-rector of the National University of Asunción, Federico Codas. Regarding the collected objects and other skeletons, the highest university body did not issue an opinion and recommended waiting for their complete revision. On the other hand, the Foreign Ministries of both countries articulated the necessary procedures for entry into Paraguay.

On 10 June 2010, the official handover of the urns took place at the Museum of La Plata. Representing the Aché people for the handover were Emiliano Mbejyvági (Linaje) and Milcíades Tayjángi (FENAP), on behalf of the Argentine State, authorities from the National University of La Plata and the Faculty of Natural Sciences were also present, as well as Argentine Indigenous and human rights organizations. Among the representatives of the Museum of La Plata, the presence of specialist Patricia Arenas, her multidisciplinary team and the Grupo Guías, [Guide Group], made up of students, stood out. That same night the remains arrived in Asunción and were temporarily stored in the Argentine Embassy for safekeeping. The following day, a first commemorative ritual was held for the remains and objects at the Museum of Memories before being transferred to their final destination: Ypetĩmi.

Aché people accompany Kryýgi’s return to the forest. Photo: Colectivo Guias

Aché people accompany Kryýgi’s return to the forest. Photo: Colectivo Guias

Reunion in the peace of the jungle

At dusk on Friday, 11 June, the urns wrapped in rave, the traditional carpet of pĩdo (palm) leaves, arrived at the community. A crowd made up of delegations from other Aché communities performed the welcoming ritual at the ceremonial center. At the entrance, flanking the path, were rows of wrestlers of the ancestral tõmumbu (the confrontation of ethical rectification) and jepy (defense and revenge). Bodies painted in black, adorned with viju (soft feathers), with javã on the head (conical cap of animal skin) and with the deadly japē (fighting spear) in their hands solemnly framed the welcome and farewell that thickened the air with emotion and awe.

Three women brought the remains, while the men grew agitated and emitted their jambu (roars). Inside, the chĩnga (lamentations and cries of complaint) and the pitiful pre'e (chanting) filled with anguish as they recollected one of the most emblematic moments lived by the Aché: the reincorporation of their ancestors who were taken by the beru (white men) and the apã proro (white men with firearms) more than a century ago. In addition, the reunion of northern and southern Indigenous groups helped to reduce the ancestral difference between the gatu, wa (the group to which the late Kryýgi mái belonged) and the iroiãngi.

A small group of men and women entered the thicket of Caazapá National Park to bury the girl and the young man who, at last, returned to their ancestral ka'a vachu (jungle) from which they were forcibly taken.

A group of men and women entered Caazapá Park to bury the girl and the young man who were finally returned to their ancestral ka'a vachu (jungle).

After the expressions of pain, recognizing the genocide, territorial dispossession, and return of the remains of those taken, the Aché people watched over their dead all night. The following day, a small group of men and women entered the thicket of the Caazapá National Park, their ancient hunting and gathering territory, to bury, in a secret place, the girl and the young man who, at last, returned to their ancestral ka'a vachu (jungle) from which they had been taken. Part of the ceremony was filmed by Argentine filmmaker Alejandro Fernández Mouján, who in 2015 released the documentary Damiana Kryýgi, tracing her journey back home.

In 2011, thanks to the exhaustive work of German journalist Heidemarie Boehmecke, the academic community reported that the skull of the girl had been located within the anatomical collection of the Charité University Hospital in Berlin. The Museum of La Plata provided all the documentation and background information and the Paraguayan embassy in Germany carried out the repatriation procedures at the request of the Aché people. Finally, in April 2012, Kryýgi was whole and at peace, cradled forever in the forest thicket where on one day, some 120 years ago, she had come into the world.