The colonial persecution of the survivors of the Avá-Canoeiro peoples, better known as Âwa, goes on. A new judicial decision has reduced their territory mostly to flooded areas with no access to the Javaés River. Conflicts have increased since Incra created a settlement in the 1990s.

The colonial persecution of the survivors of the Avá-Canoeiro peoples, better known as Âwa, goes on. A new judicial decision has reduced their territory mostly to flooded areas with no access to the Javaés River. Conflicts have increased since Incra created a settlement in the 1990s.

In 1973, exactly 50 years ago, during the military dictatorship (1964-1985), the National Indian Foundation (Funai) forcibly advanced on the eleven survivors of the Araguaia Avá-Canoeiro indigenous people. They had been evicted from their lands and powerful economic groups grabbed their territory. Three years after Funai’s attack, only five persons were alive. Now they are more than thirty people, a growth due to interethnic marriages. Since then, the self-nominated Ãwa, speakers of a Tupian language, living on the land of strangers, wait for a territory of their own where they can reunite as a community of relatives. Their violent and appalling removal was the climax of centuries of genocide and endless persecution to a people who never surrendered to the colonizer. For this they suffer brutal consequences to this day.

Despite state injustices, the Ãwa had some victories with reparatory measures. One of these is the 2016 recognition by the Ministry of Justice of the Terra Indígena Taego Ãwa (Taego Ãwa Indigenous Territory), invaded since 1997. The others are three public civil actions by the Attorney General’s Office on their behalf, requesting compensation for material and moral damages, demarcation of their land and protection of their “isolated” relatives. In March 2023, the Regional Federal Court of the First Region approved unanimously their request for compensation, albeit partially reducing its value. However, an unsettling legal decision in November 2022 regarding the demarcation process revived the old and endless colonizing oppression.

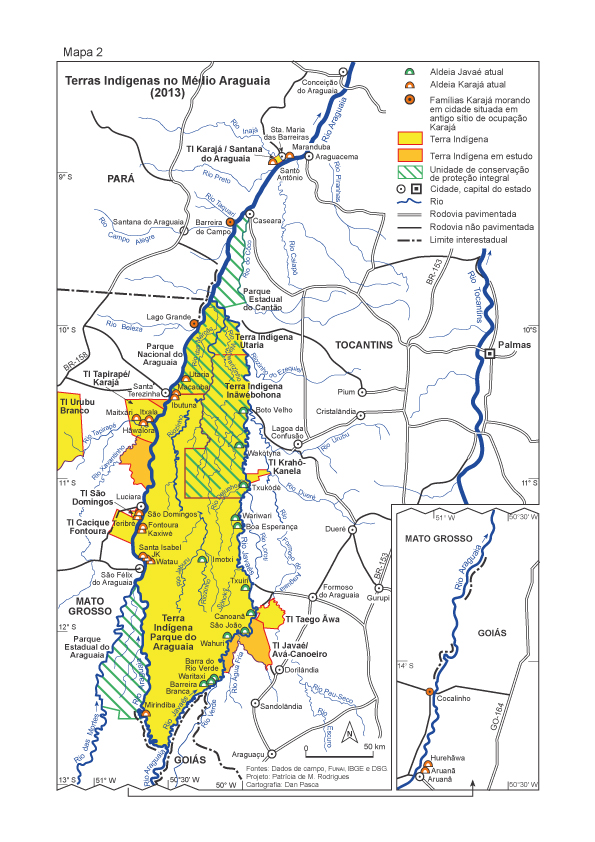

Kaukamã, the last contact survivor in the Taego Ãwa Indigenous Land. Photo: Patrícia de Mendonça Rodrigues

Kaukamã, the last contact survivor in the Taego Ãwa Indigenous Land. Photo: Patrícia de Mendonça Rodrigues

A legal decision against the Ãwa people

A federal judge from the Court of First Instance reduced in 30 percent the indigenous territory, excluding access to the region’s main river (Javaés River), thus benefitting third parties. This access is crucial for fishing, transportation and daily activities. Furthermore, such reduction would confine the Avá-Canoeiro to the only dry spot in an area constantly flooded with no access to drinking water. Although they have adapted to this inhospitable place admirably, that legal decision would lock them in a practically uninhabitable territory.

That decision produced much bewilderment, because the judge fully recognized the Avá-Canoeiro’s rights and, incontestingly, accepted the arguments in the 2012 official anthropological report presented by Funai. Based on this report, the Ministry of Justice had declared the land as indigenous. In addition, the 2014 report of the National Truth Committee emphasised the Avá-Canoeiro case. A 2021 juridical investigation confirmed the arguments contained in the anthropological report.

A federal judge from the Court of First Instance reduced in 30 percent the indigenous territory, excluding access to the region’s main river (Javaés River), thus benefitting third parties.

A federal judge from the Court of First Instance reduced in 30 percent the indigenous territory, excluding access to the region’s main river, thus benefitting third parties.

These official documents detail a sequence of errors and violent acts by the Brazilian state between 1973 and 1976. First, omitted from the Funai reports is the intemperate assault on and subsequent capture of Avá-Canoeiro people, survivors of decades of genocide in the Canuanã Estate, which resulted in the shooting and killing of the girl Typyire. Second, the use of some Shavante men as “Indian hunters” (a former colonial role) to locate the Avá-Canoeiro refuge. Then, the public and extremely embarrassing exposure to dozens of curious onlookers for weeks on end of the captives confined in a corral of the luxurious estate.

Moreover, the captors seriously neglected the prisoners’ health conditions, their low immunity due to recent contact. Pneumonia killed at least one, Tutxi whose body was taken to the city of Goiania and never returned to his relatives. On the other hand, the Indigenous Rural Guard on the Bananal Island acted to promote domination among various peoples (leading the Javaé to “tame” the Avá-Canoeiro). Repeated physical and emotional abuses are part of the Avá-Canoeiro’s traumatic memory. The survivors were then transferred to a Javaé village where they led a marginal life as if in exile.

The judge concluded his reasoning by saying that the situation requires “an extra argumentative effort” to “alter the area” so as to “make it smaller than that previously delimited by Funai.” The purpose of cutting down the territory was to benefit most of the plots included in the Caracol Settlement Project, that should lay outside the Terra Indígena Taego Ãwa. The judge further argued that he tried to “reduce the social impact caused by the displacement of over 100 families and economic impact on the region of Formoso, state of Tocantins.”

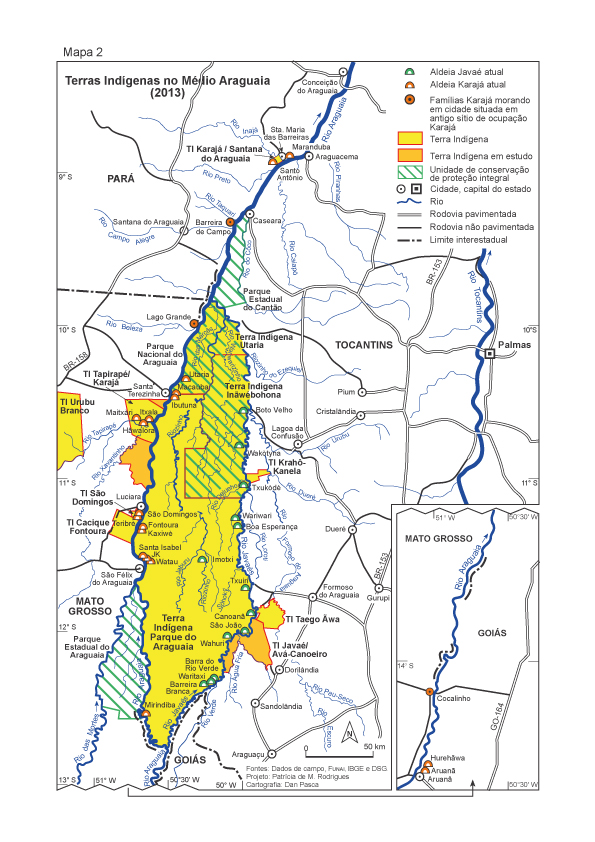

Indigenous Lands in the Middle Araguaia (2013). Map: Patrícia de M. Rodrigues y Dan Pasca

Indigenous Lands in the Middle Araguaia (2013). Map: Patrícia de M. Rodrigues y Dan Pasca

The result of an ill-conceived land policy

Due to Funai’s serious omission and neglect, in the 1990s, Incra (National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform) placed a settlement precisely in the area where Funai had attacked the eleven survivors. A judicial order had these families transferred from the regularised Araguaia Indigenous Park on the Bananal Island to an area adjacent to the non-regularised Avá-Canoeiro traditional area, which Funai was to recognise as Taego Ãwan indigenous area in 2012.

Thus, Incra moved the settlers from a regularized to a non-regularized indigenous land. With federal funds, Incra acquired areas that had belonged to Fazenda Canuanã, sold them to third parties, which, in turn, resold them back to the Brazilian state. This irregular transfer is at the root of the present-day conflict between settlers and Indians, both victims of historical omission and neglect by the state and its ill- conceived land policies. The abundant historical evidence of indigenous traditional occupation was ignored to push forward this recent and mistaken occupation.

The judge ignored the indigenous traditional occupation and defended a mistaken use of that land.

The judge ignored the indigenous traditional occupation and defended a mistaken use of that land.

In his ruling, the judge informs that only 30 families (of the 103 who now live on the Taego Ãwa Indigenous Land) are originally from the Bananal Island and have been there since the beginning of the settlement. The other family plots are state lands that have been illegally passed on to other people. Furthermore, the area in question is a floodplain (sandy and flooded most of the year) improper for cultivation. In the rainy season, most settlers rent pastures on dry ground outside the settlement. Even so, the judge ignored the indigenous traditional occupation and defended a mistaken use of that land.

Recently, in response to an appeal against that sentence, the Attorney General’s Office has argued that a First Instance Judge is not competent to define the limits of an indigenous land (it is Funai’s technical responsibility). More so, considering that the legal case only requested that the Brazilian state carry on with the demarcation process.

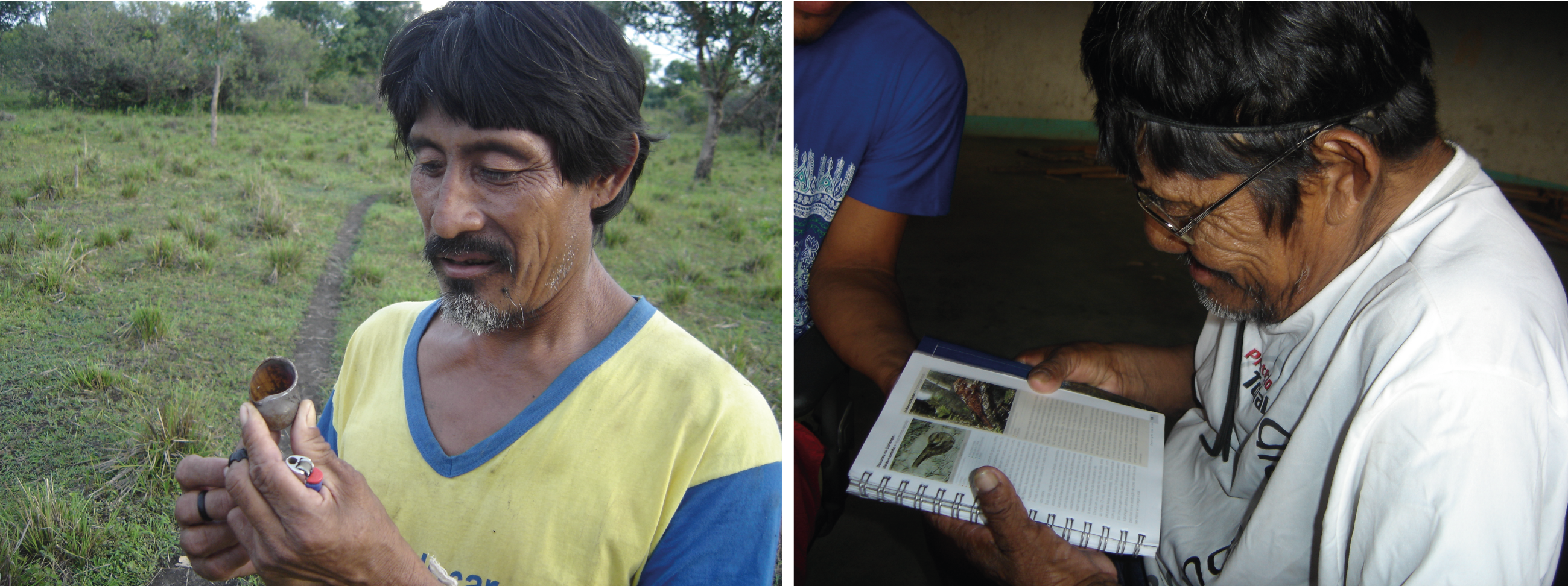

The historical leader Tutawa, in the Boto Velho village, and the Agàek community member in the Taego Ãwa Indigenous Land. Photo: Patrícia de Mendonça Rodrigues

The historical leader Tutawa, in the Boto Velho village, and the Agàek community member in the Taego Ãwa Indigenous Land. Photo: Patrícia de Mendonça Rodrigues

Oppression continues

In March 2022, still during President Jair Bolsonaro’s term, there was a conciliation hearing with the interested parties. Incra and the private occupants (of two estates) presented their proposals, which infringed upon indigenous rights. They intended to negotiate the limits of the Taego Ãwa Indigenous Land. Funai’s federal attorney, also present, did not object.

The landholders requested financial aid to build the future village on the remaining piece of indigenous land, so long as their estates were left out. Incra proposed the exclusion of all settlement plots from the indigenous land, keeping only areas of legal reserve, which are entirely flooded with no access to the Javaés River. Putting both proposals together, the Avá-Canoeiro would be left with just 7,101 hectares of a total of 29,000 hectares as was recognized by the Ministry of Justice. In other words, they would lose 75 percent of their land and be confined to 25 percent, where it is impossible to life and to bury the dead.

Land reduction in those conditions means the continuity of a long process of oppression and exile under which the Avá-Canoeiro have live from the beginning of colonization.

Land reduction in those conditions means the continuity of a long process of oppression and exile under which the Avá-Canoeiro have live from the beginning of colonization.

The Avá-Canoeiro rejected any negotiation. The proposal presented to them was so harmful and disadvantageous that is reminiscent of the times when they were known as the people in Central Brazil who most strongly resisted the coloniser and for which they were hunted down like wild animals. The Incra/landholders proposal treated the Ãwa as though the colonial and genocidal harassment was still in course, giving them a physical space where humans cannot live, the lowest place in a perverse symbolic hierarchy. The other name for this is racism. Total dehumanisation to this indigenous people celebrated in historic literature as preferring to die rather than submit.

That judicial sentence partially mitigated the colonisers’ wrath by excluding “only” 30 percent of the indigenous land and preserving a few dry and important spots. On the other hand, it cut off access to the main river, severely affecting a people known in historic literature as “Canoeists.” Land reduction in those conditions means the continuity of a long process of oppression and exile under which the Avá-Canoeiro have live from the beginning of colonization.

This article summarizes the technical note included in the report “By decision of the judge, the people of Avá-Canoeiro lose 30% of their traditional territory”, written together with the biologist Luciana Ferraz.