Esese was a baby in arms when her family was captured in their village in the 1960s. Today she is the last survivor of the Karara group first contacted on the Carará River. Marking her life and that of her relatives was rubber tapping, illegal hunting, ore mining and surveys for hydroelectric power plants on the Jatapu River. Adding to land usurpation, malaria epidemics brought in by non-indigenous workers decimated her family. Uprooted from her home on the Carará River, Esese lived in several villages, indigenous lands and towns without ever adapting to living anywhere.

Esese was a baby in arms when her family was captured in their village in the 1960s. Today she is the last survivor of the Karara group first contacted on the Carará River. Marking her life and that of her relatives was rubber tapping, illegal hunting, ore mining and surveys for hydroelectric power plants on the Jatapu River. Adding to land usurpation, malaria epidemics brought in by non-indigenous workers decimated her family. Uprooted from her home on the Carará River, Esese lived in several villages, indigenous lands and towns without ever adapting to living anywhere.

Since 1930, the Indian Protection Service (SPI in Portuguese), now Indigenous Peoples National Foundation (Funai in Portuguese) knew about the contact of voluntarily isolated indigenous peoples with rubber tappers on the mid-Jatapu, a tributary of the Uatumã River in East Amazonas state. In 1942, SPI built two Indigenous Attraction Outpost (PIA in Portuguese), one on the Jatapu near the Xowyana village, the other on the old Kahxe settlement in the Okoymoyana village.

As contact and displacements from the streams down to the Jatapu River banks, parts of these peoples opted to remain isolated on the hills. Far from preventing invasions on the Jatapu, the establishment of SPI outposts encouraged encroachment by providing shelter and goods to invaders. Furthermore, SPI personnel engaged in partnership with pelt hunters, miners and, especially, rubber tappers.

Esese and her husband Karatawa at Kahxe village (2022). Photo: Aymara Association Aymara

Esese and her husband Karatawa at Kahxe village (2022). Photo: Aymara Association Aymara

Chronicle of a capture

Rich in latex-producing trees, the region where the Karara, Esese’s people, lived was upstream from the SPI outposts. Around 1962, latex collectors captured an indigenous woman on the Cidade Velha River and took her to the SPI outpost. They took this woman and her capturers on an expedition to the Cidade Velha River to fetch other Karara Indians.

Esese reports that the karaiwa (non-indigenous) extracted latex and killed spotted jaguars on the Carará River. Hence, her relatives fled when they heard the noise of outboard motor and men arriving. However, that time the Karaiwa had put out fishnets as traps along the paths the Karara used in the forest. The younger could avoid the trap and ran to hide, but one woman and her baby were ensnared in the nets. She and those who stopped to help her were caught. Esese explains that the Karaiwa captured and took them to the SPI outpost at the Kahxe village. “They caught only five of us. Two died right away with malaria and only three survived. We didn’t like that place, we never got accustomed to it. We tried to go back to the Carará River to meet our people, but nobody was there anymore.”

Their village was empty and the other five communal houses had also been abandoned. The youths who escaped disappeared in the forest with the people of the other villages.

Their village was empty and the other five communal houses had also been abandoned. The youths who escaped disappeared in the forest.

Esese remembers that the SPI people took part in the capture. The prisoners were taken to the Kahxe outpost with her mother, grandfather and brother. “I didn’t speak Hixkaryana or Portuguese. I didn’t drink coffee, nothing. I ate my own food, cassava bread. I didn’t eat salty food.” A year later, the Karara returned to the Carará River searching for their relatives Akoko, Kamara Kana, Maxi Torowari and Karamari, who had fled.

Their village was empty and the other five communal houses had also been abandoned. The youths who escaped disappeared in the forest with the people of the other villages. Thus, Esese and her family were alone, living with people they had never met. Even so, they tried to settle next to their old village, but a bout of malaria killed her mother on the Carará River. The rubber tappers continued to work on the Carará River, malaria continued to kill indigenous people, thus it became impossible to go on living at Cidade Velha. Back at Kahxe, Esese’s grandfather and brother also died of malaria. Then her father decided to stay at Kahxe where occasionally they got some medical assistance. They returned to the Carará River several times, but saw any signs of their relatives.

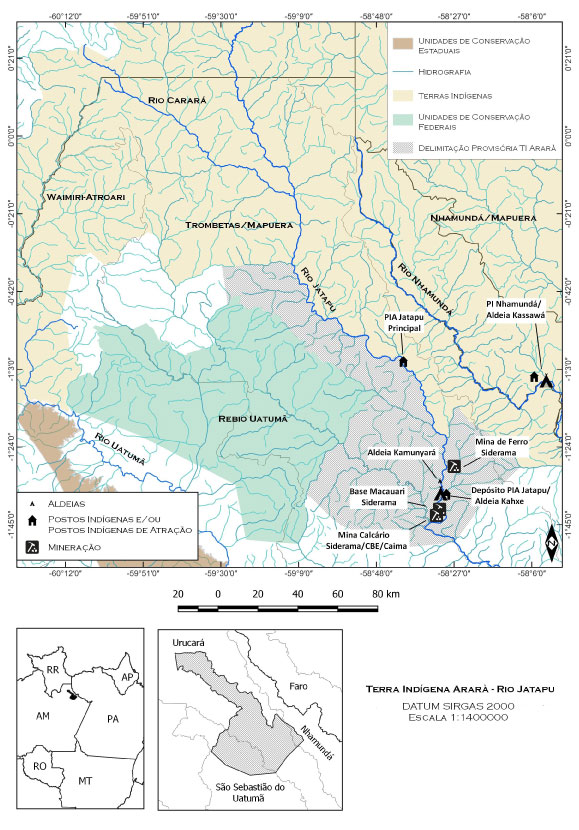

Location of the Arará Indigenous Land, indigenous peoples and main rivers

Location of the Arará Indigenous Land, indigenous peoples and main rivers

Ore mining and hydroelectric projects

Esese, her father, brother and Xenyexenye, the daughter she had with a worker, lived at the Kahxe outpost from the 1960s to the early 1980s. In 1962, the Steel Company of Amazonia (Siderama) was licensed to explore iron ore on the Jatapu River. The company built houses for the workers and opened an airstrip and offices on the banks of the Macauari River very close to the Kahxe village. As in other areas in the Amazon, the interest of the military government in promoting mining associated with hydroelectric power plants meant public funding for Siderama and research financed by federal institutions.

In 1972, Eletrobrás, a state company, carried out surveys in the Uatumã River basin and proposed the construction of three hydroelectric plants, Balbina, Katuema and Onça. The government also sponsored the National Department of Mineral Production (now National Mining Agency) the study about sulfides between 1976 and 1978 to identify tin and gold deposits in the river basin that includes the Jatapu River.

In 1975, when Siderama went bankrupt, the Superintendence for Amazonian Development (SUDAM in Portuguese) took over control of the company stocks and began to restructure it (including the Macauari headquarters), and reinitiate mining activities.

Conniving with the company, Funai abandoned the outpost and pressured the Jatapu people not to return to their villages, after several sojourns among their relatives on the Nhamundá River. They were to stay at the Kassawá Indigenous Post opened up in the early 1970s.

Esese now makes crafts to earn a living.

Esese now makes crafts to earn a living.

Funai abandons Jatapu

In 1972, Ney Land, then vice-director of Funai’s Department of Studies and Inquiries, wrote to the man in charge of the Manaus office asking for information “about the problems at the Jatapu Indigenous Post regarding the mining companies established on it.” The situation was investigated no earlier than 1976, during the fieldwork of agronomist Gertrud Rita Kloss contracted via a Funai-Radambrasil Project agreement. The Radam project was created in October 1970 with funds from the National Integration Project (PIN in Portuguese) during the term of President Emílio Garrastazu Médici. It mapped natural resources in areas targeted for colonization, power plants and mining projects. When Kloss arrived at her research site, she was astonished with what she saw. One hundred pelt hunters had invaded the region, including João Oliveira, the last SPI employee on the Jatapu.

Such invasions were no novelty on the Jatapu River. Siderama stayed there unrestricted for over a decade. “When,” said Kloss, “Siderama began to settle in the region, around 1960, there were thirty or forty Indians living at the Post. Diseases started to kill them. For this reason, a year later, they moved to the Nhamundá River, except one family. They were all from the Upper Jatapu where there are no houses left.”

Kamara Kahxe (Jaguar Rapids), where one of the Jatapu hydroelectric power stations was planned.

Kamara Kahxe (Jaguar Rapids), where one of the Jatapu hydroelectric power stations was planned.

To live without adaptation

The family that Kloss met at the Jatapu Post was precisely Esese’s family. They were still there in 1976, but Funai closed it in 1977. In 1982, Oni, Esese’s father, fearing for the lives of his daughter and granddaughter, with some Okoymoyana and Xowyana Indians (previously transferred by Funai to the Nhamundá River), decided to go to Jatapu to fetch them.

On the Nhamundá, Esese’s father married a Hixkaryana woman and had a son. Unlike him, Esese did not settle anywhere since she left Kahxe. She lived at the Jutaí village, on the Nhamundá, then moved to the town of Nhamundá and later to the town of Urucará. She tried to return to the Jatupá River in the late 1990, but her daughter was no longer used to village life and they went back to Urucará. When the Okoymoyana and Xowyana people decided to build permanent villages on the Jatapu in 2003, Esese and her daughter returned to Kahxe.

She laments never having found those who remained at the Carará River, but is convinced they are there and hopes they will be left in peace and don’t endure the suffering than fell on her own family.

She laments never having found those who remained, but is convinced they are there and hopes they will be left in peace.

Uprooted from the Carará River, Esese’s family drifted away from her relatives and places. They live their lives without being adapted to towns and alien villages, are always strangers to others. Esese is now married to an Okoymoyana widower and lives between the towns of Kahxe and Urucará where her daughter and grandchildren live. She moves between places with no real place of her own. Now she says she wants to move no longer, she will stay at Kahxe where she spent her childhood, gave birth to her daughter and where her grandfather and brother are buried.

She laments never having found those who remained at the Carará River, but is convinced they are there and hopes they will be left in peace and don’t endure the suffering than fell on her own family. When talking about them, Esese makes a point of mentioning all the children of her half-brother who lives on the Nhamundá River. She always affirm “The Karara are there!” as though to emphasize it made it possible, at last, to reunite again in a living place of their own.