Since the middle of the 20th century, protected areas have expanded all over the planet as a result of growing environmental problems. Its extension coincided by 50 percent with that of the ancestral territories. However, the “Yellowstone model” was imposed, which does not take into account that indigenous peoples live on those lands. Although indigenous knowledge has begun to be taken into account in recent years, its participation in the management of protected areas is subordinated to the state bureaucracy. In this framework, it is essential that ancestral wisdom and practices play an important role in conservation policies.

Since the middle of the 20th century, protected areas have expanded all over the planet as a result of growing environmental problems. Its extension coincided by 50 percent with that of the ancestral territories. However, the “Yellowstone model” was imposed, which does not take into account that indigenous peoples live on those lands. Although indigenous knowledge has begun to be taken into account in recent years, its participation in the management of protected areas is subordinated to the state bureaucracy. In this framework, it is essential that ancestral wisdom and practices play an important role in conservation policies.

As a result of the 2022 United Nations Conference on Biological Diversity (COP 15), the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework includes a list of 23 action-oriented targets for urgent action, to be initiated immediately and completed by 2030.

Particularly relevant is target number 3, which states: “Ensure and enable that by 2030 at least 30 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas, and of marine and coastal areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services, are effectively conserved and managed through ecologically representative, well- connected and equitably governed systems of protected areas and other effective area- based conservation measures, recognizing indigenous and traditional territories, where applicable […]”.

It wasn’t only international environmental organizations that had been working for years to achieve this goal, known as the 30 X 30 target. Economists and business people had also been considering the positive effects of expanding protected areas. Such was the case particularly of the tourism industry, especially after the slump caused by the Covid-19 lockdown. This recent development shows that the concept of protected areas continues to generate a broadly positive response.

During COP 15 the Kunming-Montreal Global Framework for Biological Diversity was adopted. Photo: CBD

During COP 15 the Kunming-Montreal Global Framework for Biological Diversity was adopted. Photo: CBD

Protected areas

Protected areas are intended to be a way of conserving biodiversity and stabilizing endangered ecosystems. They are seen as a mechanism for protecting endangered species. They date back even to before the new framework for biodiversity protection. On 1 March 1872, then U.S. President Ulysses Grant signed an act into law entitled: “AN ACT to set apart a certain tract of land lying near the headwaters of the Yellowstone River as a public park.” Thus the first national park was born, albeit not officially yet known as such.

Yellowstone is set within a breathtaking landscape that was at that time still far removed from the advancing frontier of Anglo-Saxon civilization. And yet the territory was not devoid of people: the Crow, Shoshone, Nez Percé and other Indigenous groups were all immediately expelled from the area by the U.S. Army. At least 27 Indigenous Peoples had an historical connection to the environmentally protected area created by Grant.

In the opinion of John Muir, there was no place for “savages” in a nature seen as original, divine and sublime. God had preserved the natural wonders to impress them upon the Christian settlers arriving from the “Old World”.

In the opinion of John Muir, there was no place for “savages” in a nature seen as original, divine and sublime.

The world’s first national park was the result of the activities and efforts of a certain John Muir, an early advocate of wilderness preservation in the United States. Muir was a Christian apostle who believed there to be a divine presence in nature: supposedly an original and pure nature.

Muir thus profoundly influenced the way Americans continue to this day to understand their relationship with the natural world. In his opinion, there was no place for “savages” in a nature seen as original, divine and sublime. God had preserved the natural wonders to impress them upon the Christian settlers arriving from the “Old World”.

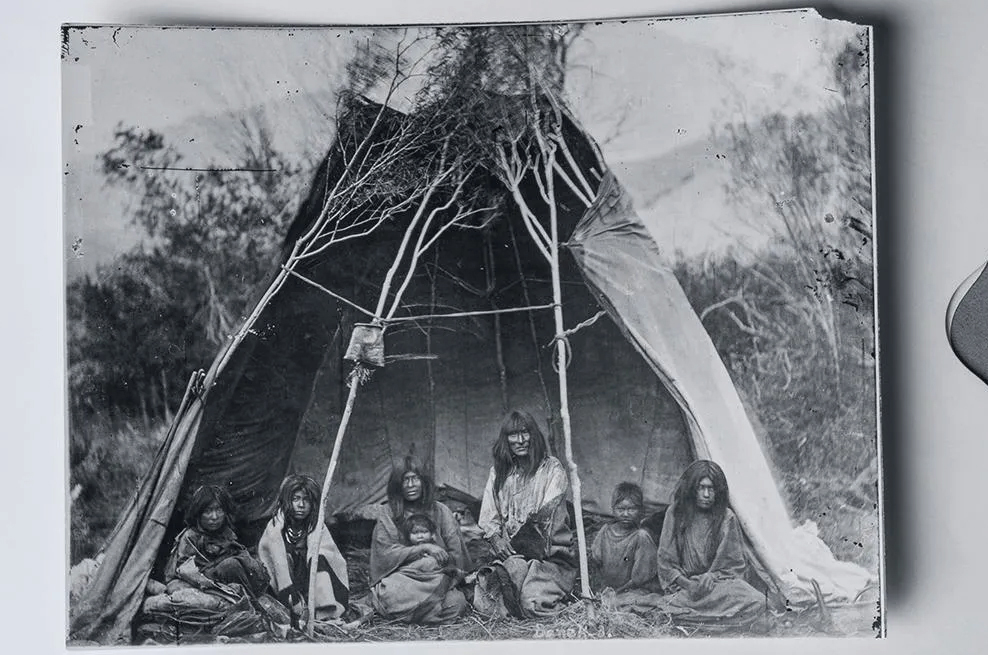

The Shoshone were one of the Indigenous Peoples expelled by the US Army from Yellowstone. Publicly, it was claimed that there were no natives in the national park. Photo: William Henry Jackson

The Shoshone were one of the Indigenous Peoples expelled by the US Army from Yellowstone. Publicly, it was claimed that there were no natives in the national park. Photo: William Henry Jackson

The Yellowstone model

Since the mid-20 th century, the world’s environmental problems have loomed ever greater and there has been a global boom in the creation of new protected areas. Between the years 1951 and 2000, the expanse of land-based protected areas increased from some one million square kilometres to over 13 million. The number of protected areas increased from 20,000 to 100,000. And yet the model used was the Yellowstone model, which thus became the epitome of a protected area based on the idea of protecting “pure nature”.

The Yellowstone model has the following features: protected areas are established unilaterally by the State; their design and management is in the hands of government agencies, often working with environmentalists; the lands and biodiversity are considered to be the property of the State; the knowledge base for their management takes its basis in the biological sciences; its purpose is nature conservation without humans; socio-cultural environments are not considered; and, finally, their creation takes place along so-called objective scientific criteria, i.e. a high degree of endemic biological diversity and a high level of threat to this diversity.

Most of these protected areas are superimposed on territories that have traditional and longstanding human populations. Estimates suggest that a full 50% of these areas overlap with the traditional territories of Indigenous Peoples.

Most of these protected areas are superimposed on territories that have traditional and longstanding human populations.

Most of these protected areas are situated in parts of developing countries that may be remote but which are neither wild nor uninhabited. Indeed, these areas are superimposed on territories that have traditional and longstanding human populations. Estimates suggest that a full 50% of these areas overlap with the traditional territories of Indigenous Peoples. Most of these populations were considered unimportant for the purposes of protected areas because these areas are created on the basis of Western scientific criteria of “nature” and “conservation”. And it is the State’s exclusive – and excluding – power to define and manage how they operate. The creation of protected areas is effectively a process of extending State control over spaces that the State claims.

At the same time, protected areas become a vehicle for coercive assimilation and take on a kind of “civilizing mission”. This colonial premise has strong historical and philosophical roots: John Locke, the father of modern liberalism, defended individual property rights as founded on natural law. He contended that the fruits of labour are one's own because each person has worked for it, especially by transforming nature into regions of (agri-)culture. The farmer thus has a natural property right over the land because exclusive ownership is supposedly necessary for production. From this perspective, people who do not cultivate the land and fence it do not have legitimate ownership. The Indigenous Peoples of the Americas were therefore seen as nomadic tribes, harvesting fruits and animals from the natural world but without making any significant contribution in return.

Maasai pastoralists in Tanzania are fighting to prevent the government from creating a conservation area for sport hunting. Photo: Landportal

Maasai pastoralists in Tanzania are fighting to prevent the government from creating a conservation area for sport hunting. Photo: Landportal

Indigenous territories: the most biodiverse on the planet

This colonialist approach to liberalism has evolved into a general theory of the legitimacy of property, one that denies Indigenous Peoples the right to their lands. This social philosophy of enlightenment included a certain vision of nature that served as a theoretical basis for justifying the establishment of a new civilization, that of the European settlers: the natural world was seen as a category of vacuum domicilium (wasteland) and only human labour could transform it into an object of ownership.

The social institutions of the original peoples of the Americas were not considered to be a political order; their relationship to the land was not recognized as an adequate condition for claiming ownership; and nor was their system for handling internal conflicts seen as a legitimate legal order. In short, the enlightened philosophers considered that the original peoples lived in a state of nature and not in a civil society, an idea that even became enshrined in the legal doctrine of the 19 th century. Although the Indigenous Peoples were not defined as non-human, the conquerors did believe that they needed to be subdued and “governed” by European institutions. In this way, the concept of wasteland thus formed a prerequisite for the expansion of colonial institutions.

Research indicates that some 80% of the world's biological diversity exists in regions that remain under the control of Indigenous Peoples.

Research indicates that some 80% of the world's biological diversity exists in regions that remain under the control of Indigenous Peoples.

The overlap that exists between biodiverse ecoregions and Indigenous territories has not, however, happened by chance. Both the diversity and the ecological richness of these areas are the result of Indigenous Peoples’ ways of life and social institutions. The spiritual connections they have with their habitat, their communal use of resources and customary ways of managing forests, mountain areas, water resources and wildlife have all preserved the genetic and ecological diversity and even fostered its development in a large number of places.

Recent natural science studies confirm this. Lands often characterized as “natural”, “intact” and “native” generally demonstrate long histories of use by traditional societies. Today, territories under Indigenous management are recognized as having the highest biodiversity on the planet, even greater than areas with a total absence of human population. Research indicates that some 80% of the world's biological diversity exists in regions that remain under the control of Indigenous Peoples. A full 92% of Indigenous and local community lands surveyed act as “net carbon sinks”, meaning that they absorb more carbon dioxide than they emit.

During the V World Parks Congress in Durban (IUCN), one of the demands formulated by Indigenous People was to give priority to conservation based on community tenure in Africa. Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, reference mbororo. Photo: @hindououmar

During the V World Parks Congress in Durban (IUCN), one of the demands formulated by Indigenous People was to give priority to conservation based on community tenure in Africa. Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, reference mbororo. Photo: @hindououmar

Compatibility between protected areas and Indigenous territories

The current extinction crisis, this global threat to biological diversity, is not the result of an invasion of regions of uninhabited nature. It is rather the destruction of cultural landscapes, inhabited and protected by Indigenous societies. Paradoxically, the expansion of protected areas has contributed to this destruction by relocating or annihilating the guardians of the land, not to mention the losses associated with their ancestral knowledge and practices, as well as their systems of social organization.

Environmental policy has only recently begun to be influenced by these developments. In 2003, for the first time, Indigenous Peoples' representatives participated in the V th World Parks Congress in Durban (South Africa): a key international forum for the protected areas agenda, sponsored by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The Indigenous people presented a series of actions: they claimed recognition of their customary rights to their territories and resources; they denounced their forced” displacement as cultural and physical genocide; and they demanded the return of their lands. It is important to note that they did not question environmental policy per se but rather emphasized the need to make the protection of nature compatible with cultural diversity.

Effective environmental conservation and protection require an alternative path. Indigenous voices should not only be heard, their traditional knowledge and practices should form the basis of conservation.

Indigenous voices should not only be heard, their traditional knowledge and practices should form the basis of conservation.

Indigenous Peoples have been increasingly heard in the management of protected areas in recent decades. Environmental organizations have promoted the idea of co-management, understood as joint work based on traditional knowledge and “modern park management” in which Indigenous people are “stakeholders”. And yet protected areas continue to operate under a governance structure in which the Indigenous population is subordinate and the final decisions remain the purview of the State bureaucracy.

Effective environmental conservation and protection require an alternative path. Indigenous voices should not only be heard, their traditional knowledge and practices should form the basis of conservation. Protected areas should run on the basis of the peoples’ right to self- determination. Their creation and management requires free and informed consent.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Framework refers to recognizing Indigenous and traditional territories “where applicable”. Only the coming years will show whether many Indigenous Peoples’ fear of their land being grabbed under the pretext of environmental policy is justified or whether, instead, recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ indisputable significance to conservation will lead to a new environmental policy.