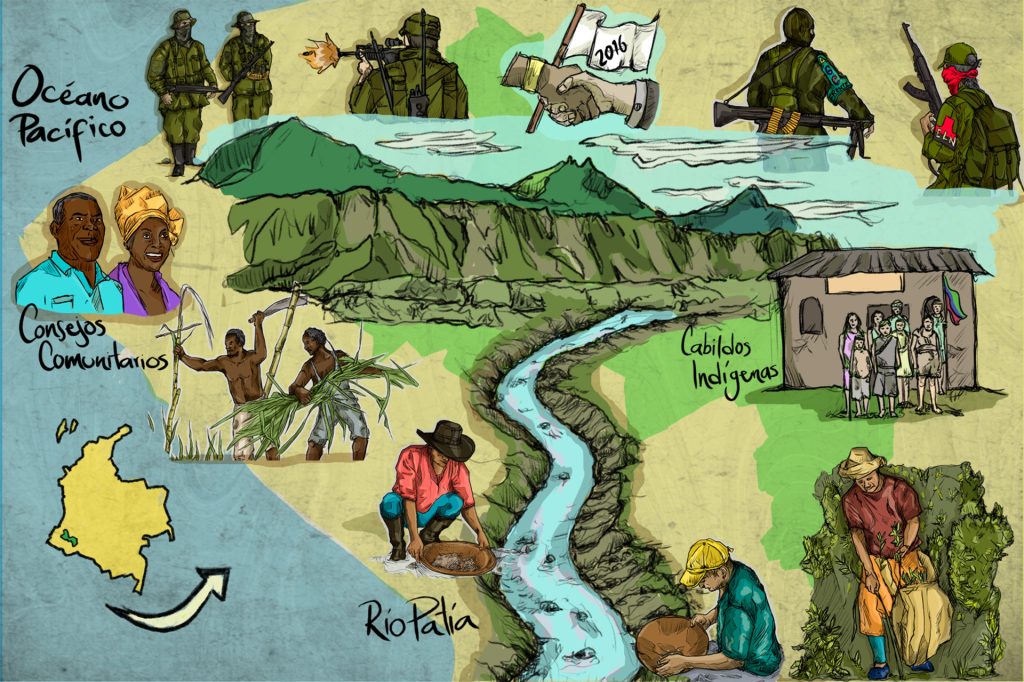

In southern Colombia, especially in the department of Cauca, criminal organizations control territories and are the scene of bloody hostilities. The clashes are mainly over marijuana and coca growing areas and control of drug trafficking routes. As a result, Indigenous Peoples and Afro-Colombians suffer from the forced recruitment of minors, threats of “plata o plomo” (“silver or lead”) and the murder of leaders. However, not all of this is through violence: while a day laborer earns between 30,000 and 50,000 pesos per day, a coca leaf picker can earn between four and five times as much as a day laborer.

A report by the Ombudsman’s Office at the end of 2023 reveals that 428 municipalities, just over a third of Colombia’s municipalities, are under the control of drug traffickers, guerrillas or paramilitaries. Almost all of Colombia’s 87 Indigenous Peoples and Black communities are in this vast territory. While criminal activities have a high impact at the local and regional level, they have also expanded their tentacles into national politics as they have penetrated many of the country’s institutions. In this way, they have made these institutions susceptible to money that comes and goes, leaving a “Sicilian” image in the social environment.

Prior to the signing of the Peace Agreement in 2016, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) dominated these territories. Since their demobilization, several armed groups now rule these regions: the leftist self-styled National Liberation Army (ELN); the Nueva Marquetalia, a splinter group of the demobilized FARC led by Iván Márquez; the Dagoberto Ramos and Jaime Martinez columns, also from the FARC, with a terrorizing presence in the Cauca department; the Central General Staff (EMC), a federation of FARC splinter groups, commanded by Gentil Duarte and Iván Mordisco (an alias).

There is also the reborn Popular Liberation Army (EPL); the alliance of paramilitary groups, self-styled Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC) and called by the government as “Clan del Golfo” [“Gulf Clan”]; there is also the presence of the Mexican cartels Sinaloa, Jalisco Nueva Generación and Zetas. These groups are engaged in a wide range of illegal activities: drug trafficking, smuggling, arms trafficking, illegal mining, kidnapping, extortion and the extraction of state revenues.

A geopolitical control of cruelty

Using Ulrich Oslender’s article, Geographies of Terror: A Framework of Analysis for the Study of Terror, this space would be a “geography of terror,” as disputes over control of the region have put Indigenous Peoples in a cross-fire zone. For this criminal network to function, the method employed by criminal organizations is to act cruelly against the local population to wrest the drug business from their “competitors” and to socially control a territory. This form of barbaric geopolitical control is practiced by all armed groups.

As a result, Indigenous Peoples and Afro-Colombians suffer the forced recruitment of minors, threats and the murder of leaders, for the mere reason of opposing the illicit cultivation of coca and marijuana in their territories. Indigenous people from Nasa say that between 2021 and 2022 at least 300 young men and women were recruited, aged between 12 and 15 years (the figure is an underreporting, as many are not reported for fear of reprisals). The procedure for the “luring” of these minors is simple: they are offered things that Indigenous people’s families cannot give them: clothes, brand-name shoes, money, high-end cell phones and even motorcycles. But recruitment is forced. It is done under the threat of “silver or lead” [“plata o plomo”].

The young people are offered things that Indigenous people’s families cannot give them: clothes, brand-name shoes, money, high-end cell phones and even motorcycles. But recruitment is forced. It is done under the threat of “silver or lead.”

The recruitment of Indigenous people is forced. It is conducted under the threat of “silver or lead”.

Most of these young people are used in the coca agribusiness and narcotics trafficking trades: planting, fumigation, leaf collection and cocaine processing. On more than a few occasions, the young women are destined for sex trafficking for the troops. The Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC) denounces that some young people are murdered and their bodies disappeared. There is even a growing number of Venezuelans who are recruited for drug trafficking, but there are no precise data or traces in cases of disappearance.

Although the CRIC is trying to recover these young people through their kiwe thegnas (Indigenous guards), it is not an easy task because they do not know the armed actor that recruited them, and the armed organizations do not know the Indigenous authorities. “Before, when the FARC was the only armed actor, it was possible to establish a dialogue. Now there are many groups that take the boys, and it is not easy to talk to them,” explains a leader of the Association of Indigenous Councils of Northern Cauca (ACIN).

The impact of drug trafficking in the territories of the region

The criminal environment is also forged by the imaginary well-being and prosperity brought about by the coca leaf. While forced recruitment is responsible for part of the growth of armed groups that reach 6,000 members, many others are attracted by the income or rewards obtained: while a day laborer earns between 30,000 and 50,000 pesos per day for field work, a coca leaf picker (raspachín) can earn between four and five times as much.

A study conducted in 2022 by the Nasa people of Northern Cauca reveals that, given the precariousness of the Indigenous people’s economies, where 80% of the families live below the poverty line, it is the young population that is mostly employed in these trades. The coca industry also offers great advantages for landowners. Many farmers, and not a few Indigenous people, have been giving up their land due to the enormous increase in the price of land, a situation that has been altering the production system in the region. The increase in the area under illicit crops, such as marijuana and coca, and the consequent reduction in agricultural production, has led to higher food prices. For example, Cauca produces more than 50% of the country’s marijuana and a large part of these crops are in Indigenous reserves.

The expansion of drug trafficking in Indigenous people’s territories generates violence. The Institute for Development and Peace Studies (Indepaz) reports that in the last four years 89 Indigenous leaders have been assassinated in Colombia, most of them were Nasa Indians from Cauca.

The advance of drug trafficking generates violence. In the last four years 89 Indigenous leaders have been assassinated in Colombia, most of them Nasa del Cauca Indigenous people.

A collateral damage of the recruitments is that some Indigenous militia members, either for the prestige that money brings or for the feeling of power that weapons offer, end up imposing norms in their own communities, ignoring the traditional internal legal system and restricting the political decisions of their organizations. In this way they internalize the violent practices of their aggressors. Following his visit to Colombia from March 5 to 15, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Francisco Cali Tzay, pointed out the indoctrination of young Indigenous people used as informants, which has led to the splitting of communities and the weakening of their governments.

The spread of drug trafficking in Indigenous people’s territories generates violence. The Institute for Development and Peace Studies (Indepaz) reports that 89 Indigenous leaders have been assassinated in Colombia in the last four years, most of them Nasa Indians from Cauca. After the signing of the Peace Agreement in Havana, the department of Cauca is also the most affected by the murder of social and community leaders: out of 1,300 victims, 309 are from Cauca.

A challenge for Indigenous People’s organizations

For the Nasa people, coca is a sacred plant. As such, it is rooted in ancestral practices and religious ceremonies, and is commonly found in their gardens. However, cocaine production has colonized traditional forms of Indigenous people’s production and has caused serious cultural, territorial and identity disruptions. In all fairness, it must also be admitted that the revenues have improved the living conditions of many Nasa families. A situation that has led some leaders to consent to and tolerate the development of this alienating economy. Even knowing the challenge that falls on those families that are compelled to get involved in the drug trafficking business.

Consequently, the power of the drug economy has become the main threat to the lives of Indigenous Peoples in Cauca. Paradoxically, the most recent Indigenous people’s struggles have been to “liberate Mother Earth” from sugarcane monocultures in the territories. On other occasions, Indigenous people in Cauca have successfully weathered attempts to undermine their power over their lives and territories. Let us remember the tenant farmer Manuel Quintín Lame, who unified the Nasa into a single group to prevent the dissolution of their reservations, or Don Juán Tama, a historical hero of the Nasa, who led the 18th century struggles to defeat the encomenderos who usurped their lands, encouraged by the Spanish Crown.

“Many Quintines will be born,” goes the hymn of the Cauca Indigenous guard. And they are right because both Indigenous people and Afro-Colombians need to unite once again if they want to defeat the drug economy. Cocaine and marijuana production is having a serious impact on their way of life, increasing alcohol and substance consumption among the younger population, undermining community governance and affecting control over their territories. As if this were not enough, deforestation and contamination of rivers during the planting, fumigation and cocaine production stages has led to what Indigenous people call the “disarmament of the territory.”

Efraín Jaramillo is a Colombian anthropologist and has accompanied the struggles of Colombian Indigenous people's organizations for the last 40 years. He was advisor to the Indigenous delegate Alfonso Peña Chepe to the 1991 Constituent Assembly.

The Jenzerá Work Collective (Colectivo de Trabajo Jenzerá) is an interdisciplinary and interethnic group founded in 1998 by people with extensive experience in accompanying Indigenous Peoples, Afro-Colombians and campesinos in various regions of Colombia.