In the last decade, the Mayangna, Miskitu, and Rama peoples have seen an escalation of interethnic, political, and environmental violence in their territories, surpassing the capacity of their justice systems and conflict resolution mechanisms. Beyond the traditional disputes with mining companies, they are currently facing conflicts with individuals who arrive to illegally settle in their territories with the aim of establishing livestock projects. Additionally, there is interference from state apparatuses through partisan political operators who threaten the autonomy and the right to self-determination of indigenous peoples.

On Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast, in the Muskitia region, three indigenous peoples reside: the Mayangna, Miskitu, and Rama. Of the 23 demarcated territories in the country, these three peoples hold 21 titled territories, while the other two belong to the Afro-descendant Creole and Garifuna peoples. Together, they possess 32% of the national territory. Recently, the lack of land on the Pacific coast and the exportation of meat have increased the invasion of their territories by settlers.

Like other indigenous peoples around the world, the Mayangna, Miskitu, and Rama face significant structural conflicts of an environmental, ethnic, and political nature. The first is related to the advancement of agro-livestock projects in their territories; the second is related to high levels of non-indigenous presence leading to acculturation; and the third is related to the existence of dual structures of authority within the same territorial unit.

In his article “Violence: Cultural, Structural, and Direct,” Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung explains that violence can be seen as a deprivation of fundamental human rights to life, wellbeing, happiness, and prosperity. Additionally, it also diminishes the satisfaction of basic needs below what is possible. This is the cultural and structural violence currently being experienced by Nicaraguan indigenous peoples. Consequently, the eradication of violence and the reconstruction of peace are necessities for the indigenous populations of the Caribbean Coast.

Between the massacres and the lack of land demarcation

As is well known, Nicaragua has been engulfed in a spiral of structural violence that affects fundamental human rights. In the specific case of the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean Coast, the conflicts revolve around the deprivation of territorial rights, the plundering of natural resources, land dispossession, and the violation of their autonomy. This infringement of rights comes from both the state and third parties present in the territory.

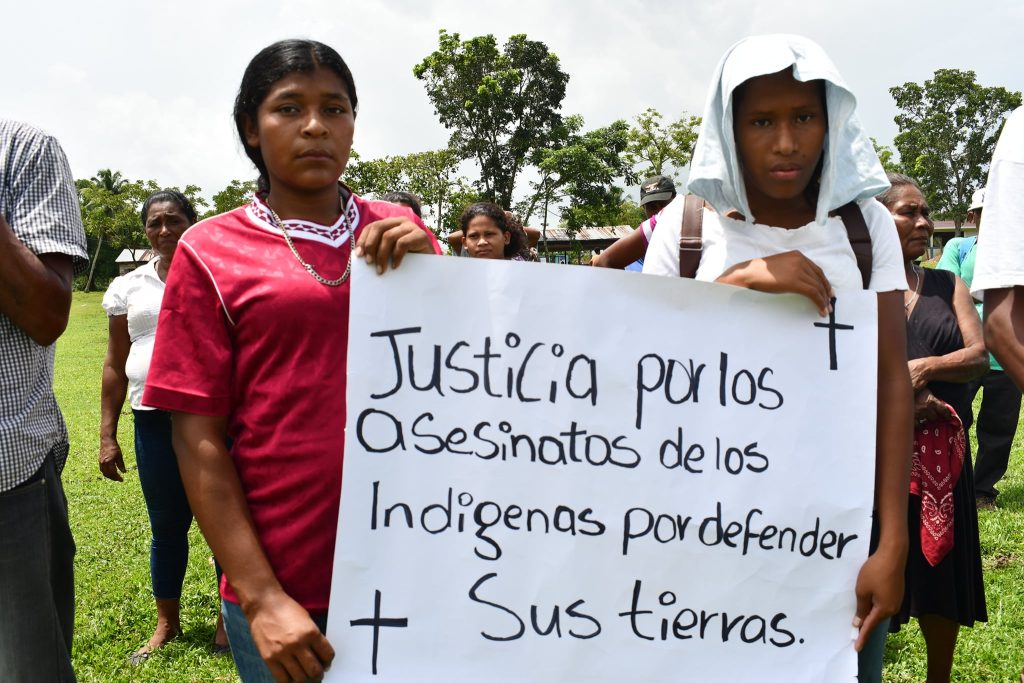

In recent years, the escalation of violence has targeted the burning of Indigenous communities and, in the worst cases, massacres of Mayangna and Miskitu Indigenous peoples. The causes of these conflicts include the absence of territorial security measures and, particularly, the delay in implementing the land titling process established by Law 445 on the Communal Property Regime.

While the Indigenous peoples resist hostile actions and territorial dispossession, the settlers seize lands through fraudulent and violent methods. Meanwhile, the state neglects its responsibility to ensure community and territorial security.

While the Indigenous peoples resist hostile actions and dispossession, the settlers seize lands through fraudulent and violent methods.

The document Challenges for Mayangna Territorial Governance in the Face of Closing Spaces for Autonomy in Nicaragua indicates the lack of land titling has contributed to progressive invasions that result in the eviction of Indigenous lands, threaten the disappearance of Indigenous territories, and promote their conversion to private property for agricultural activities (mainly cattle ranching), logging, and mining for the international market.

In these conflicts, the opposing parties are the Mayangna, Miskitu, and Rama communities on one side, and the mestizo settlers and the state on the other. While the Indigenous peoples resist hostile actions and territorial dispossession, the non-indigenous settlers seize lands through fraudulent and violent methods. Meanwhile, the state of Nicaragua neglects its responsibility to ensure community and territorial security.

The conflict between cultural identity and economic interests

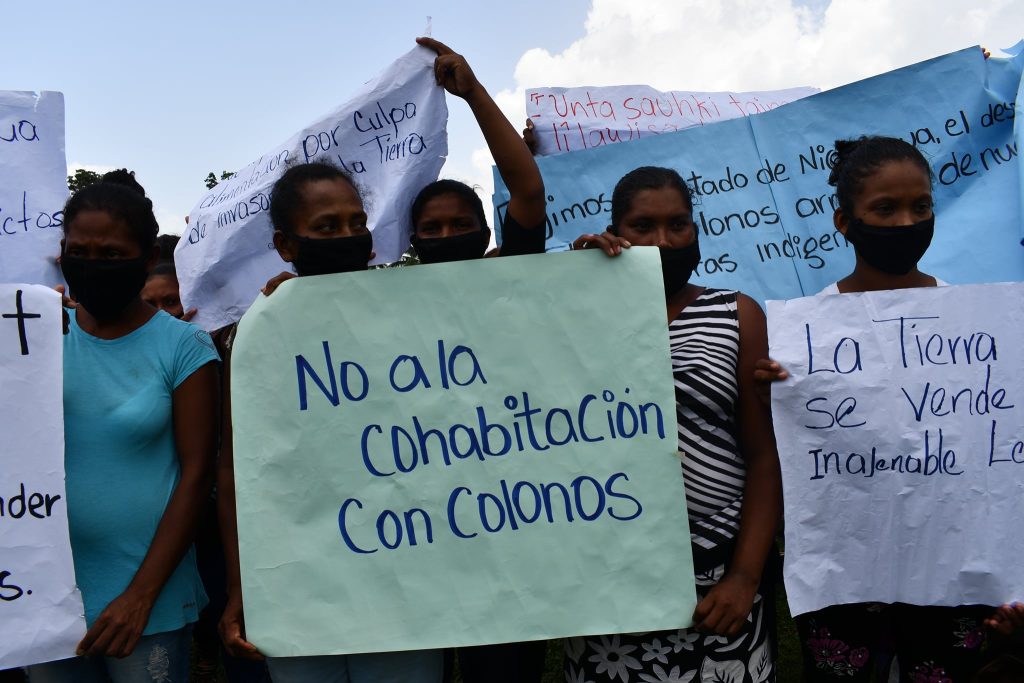

In Nicaragua, conflicts arise when communities protest against the illegal occupation of their territories by non-indigenous criollos or mestizos. The Indigenous peoples argue that the logic of private property held by settlers is incompatible with the logic of collective property of the communities. In contrast, settlers claim that there is no longer suitable land for production in the Pacific region since the lands are arid, they are forced to sell their plots to the economic elite of the region and then move towards the eastern part of the country, the Caribbean where there are extensive forests.

These lands are particularly suitable for extensive cattle ranching: beef exports rank third in Nicaragua’s export categories behind garments and raw gold. Thus, the export of beef puts pressure on evictions. However, the lands are also suitable for the establishment of monocultures of beans, corn, cocoa, and African palm. The resulting social conflict between indigenous and non-indigenous people is not only ethnic, cultural, and racial but also economic. As a result, many conflicts have escalated to violent levels, such as the massacres in the Mayangna Sauni As territory (2020-2024) and in the Miskitu territories (2015-2020).

Beyond its economic nature, the conflict is also linked to identity. On one side, indigenous peoples defend their cultural rights, collective land tenure, and harmonious relationship with Mother Earth. On the other side, mestizo settlers are interested solely in economically exploiting the land, while the State implicitly supports the economic project of the settlers, which contributes to the growth of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Thus, the indigenous worldview clashes with economic interests.

The (non) role of the State

For its part, the Nicaraguan state has been unable to meet the demands of Indigenous communities regarding the completion of the titling process for Indigenous lands. Consequently, this has become a model of prolonged social conflict. The differences between indigenous peoples and settlers are ontological and, therefore, non-negotiable. For Indigenous communities, it is even a matter of life or death because without territory, there is no life. The conflict is difficult to resolve because the law itself prohibits the negotiation of indigenous lands.

In their work Conflict Resolution: The Prevention, Management, and Transformation of Lethal Conflicts, researchers Oliver Ramsbotham, Tom Woodhouse, and Hugh Miall point out: “Most states suffering from prolonged conflicts tend to be characterized by incompetent, narrow-minded, fragile, and authoritarian governments that are incapable of meeting human needs.” This definition perfectly describes the lack of willingness on the part of the Nicaraguan state to engage in dialogue with the conflicting parties. Even the indigenous peoples have called for dialogue countless times because they consider it fundamental to resolving these conflicts.

The Nicaraguan state is part of the problem and, therefore, cannot be a mediator. One possible alternative would be the involvement of an international third party.

Given the lack of response from the Executive Branch, a judicial route should be the most practical path to resolve the conflict. However, this also does not work because the Nicaraguan state has economic interests in the Caribbean Coast. Consequently, the most useful tool would be dialogue between both parties, but there are two obstacles: first, indigenous peoples need to preserve the territory to safeguard their relational identity with nature; second, as we said, the law itself prohibits it.

As has been shown, the Nicaraguan state is part of the problem and, therefore, cannot be a mediator. One possible alternative would be the involvement of an international third party: there are special procedures for Indigenous affairs at the United Nations that could facilitate dialogue between the State and Indigenous peoples. On the other hand, Indigenous communities, with the advice of Non-Governmental Organizations, could establish bilateral conversations with the state as long as there is openness and willingness on both sides.

Peace as the path to freedom

Among the possible solutions to the land conflict is the promotion of agrarian reform that benefits the peasantry and allows for their relocation to other non-indigenous areas. Alternatively, contractual arrangements could be established so that settlers can remain on Indigenous lands under the condition that they respect the ownership rights of the communities. Thus, third parties would have the opportunity to occupy these lands as tenants and not as owners (as they have been pretending to be so far).

As we have discussed, the conflicts experienced by the Indigenous peoples of Nicaragua have led to worrying levels of violence. A Miskitu indigenous leader, whose identity we will not disclose for security reasons, explains that peace is the freedom to decide their own destiny, what to do, and what not to do: “Today we no longer have these conditions. We can no longer go freely to our plots. We can no longer freely choose our authorities; we are divided by political party issues”.

A Mayangna community member shares a similar viewpoint: “Peace is the harmonious coexistence among families, among communities, and with nature. Today, we do not live in harmony due to the unrest caused by the presence of many people from other cultures in our community”. In the Caribbean Coast, there is no peace, no harmony, no satisfaction, and no happiness in the community environment. The challenge is to reconstruct the peace we have lost.

Larry Salomon Pedro is a Mayangna indigenous person from Nicaragua and a Master's student in Conflict Resolution, Peace, and Development (CRPD) at the United Nations-mandated University for Peace.