Although its reform represents progress for the national legal framework, the amendments come 30 years too late and raise concerns about their potential implementation. The main challenge lies in the lack of financial and administrative capacity-building for Indigenous peoples to fully exercise their autonomy. Additionally, the reform still does not guarantee that prior consultation will meet international standards and move beyond being a mere administrative formality, as it currently stands. In practice, there is a risk that the reform may end up being a symbolic gesture without bringing about deep structural changes in the economic policies that affect Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities.

The 2024 constitutional reforms on the recognition of Indigenous and Afro-Mexican peoples as collective subjects of public law came 30 years too late. It was a long-standing demand of the Indigenous movement, first forwarded by the 1996 San Andrés Accords. Since that time, the conditions for the recognition and implementation of these rights have changed drastically, becoming increasingly unfavorable for Indigenous peoples and, now, also for Afro-Mexican communities.

The reforms introduce several key provisions: recognition as subjects of public law with legal personality and their own assets; autonomy to manage public resources; the right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consultation for projects impacting their territories; and protection of their cultural and territorial heritage. The reform also includes specific sections on the rights of Afro-Mexican peoples and a separate chapter addressing the rights of Indigenous and Afro-Mexican women. While many of these rights already have international recognition, they have now been incorporated into Mexico’s legal framework, which remains largely positivist and state-centric.

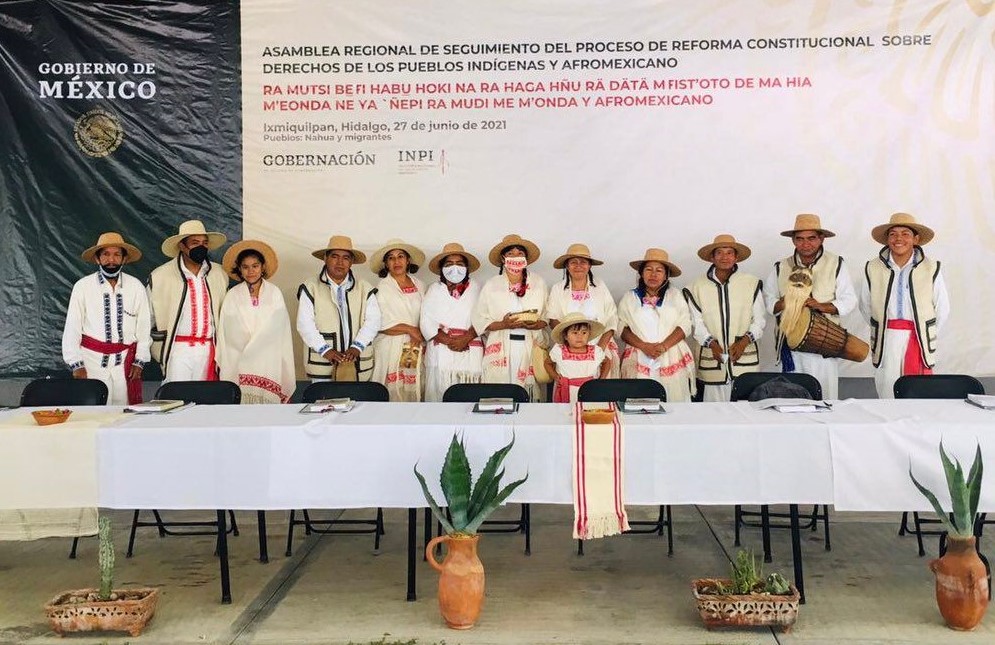

The process of drafting the reform was complex. It was led by the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI), which carried out consultations with thousands of community authorities. However, it did not meet the standards of true consultation as set out by the expert mechanism. Consequently, rather than a genuine consultation, it can be said that the process amounted to a series of forums where opinions were simply recorded.

Challenges and criticisms of the constitutional reform

The recognition of Indigenous and Afro-Mexican peoples as public law entities with legal personality and their own assets presents a series of challenges and criticisms that must be addressed to ensure it does not remain a legal framework without real impact on their living conditions.

First, although the status of “public law entity” grants communities greater control over managing their resources, including the ability to directly receive and manage public funds, it does not automatically translate into empowerment. A lack of administrative capacity, infrastructure, and access to proper training can significantly limit their ability to exercise this right effectively. Without state support in financial management and public administration training, the promised autonomy may become hollow and, and worse, result in mismanagement or dependency on external actors.

While the reform marks an important step toward formalizing collective rights, there is a risk that this recognition could be used as a rhetorical tool without the State’s genuine commitment.

Another key criticism of the reforms is the potential political instrumentalization of the recognition of legal personality as collective public law entities. While the reform marks an important step toward formalizing collective rights, there is a risk that this recognition could be used as a rhetorical tool without the State’s genuine commitment to equipping communities with the necessary means to exercise these rights. There have been numerous instances where legal recognition has not translated into tangible improvements in people’s lives, fostering frustration and distrust toward the government.

The recognition of communities’ own assets is another essential but complex component. Allowing communities to autonomously manage their assets means they can make decisions regarding the use of their lands, as well as their natural and cultural resources. However, in practice, this autonomy can be hindered by structural inequalities that have left Indigenous territories vulnerable to the pressure of external actors seeking to exploit their resources for extractive or infrastructure projects. This is further exacerbated by the presence of organized crime. Without clear mechanisms to protect these assets, the recognition of their autonomous management could end up being more symbolic than substantial.

The risk of consultations continuing to be conducted as they have been up to now

Free, Prior, Free, and Informed Consultation is one of the key pillars of the constitutional reform, as it aims to ensure that Indigenous and Afro-Mexican communities actively participate in decisions affecting their territories and ways of life. However, despite its importance, this mechanism faces numerous critical challenges that undermine its effectiveness and, in some cases, perpetuates existing inequalities. For example, protocols are often designed by the State without the involvement of the communities themselves, as was the case with the so-called consultations on the misnamed “Maya Train.”

The main risk is that consultations will continue to be carried out in the same manner as before, meaning they remain merely procedural and fail to comply with international standards established by ILO Convention 169 and the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. On many occasions, prior consultations conducted in the context of megaprojects have been superficial, without ensuring that communities genuinely understand the scope of projects and their long-term impacts. This has led to distrust toward the State and project proponents, weakening the mechanism’s purpose and turning consultations into a formality rather than a meaningful exercise of self-determination.

Corporations and the State often possess greater resources and access to technical information, placing communities at a disadvantage when it comes to negotiating or fully understanding the impact of projects.

A second risk is the lack of genuine consent from the communities. While the reform establishes the right to consultation, it does not always guarantee that communities have the option to reject projects they deem harmful. In many instances, consultation is employed as a mechanism to legitimize decisions that have already been made well in advance by the State or corporations, reducing communities to mere spectators in a process that does not necessarily respect their will. This creates a fundamental contradiction between the right to self-determination promoted by the reform and the actual practice of how these processes are conducted.

Furthermore, the power imbalance between communities and economic actors is another significant obstacle. Corporations and the State often possess greater resources and access to technical information, placing communities at a disadvantage when it comes to negotiating or fully understanding the impact of projects. Without adequate support—such as interpreters, legal counsel, or specialized advocates—communities are vulnerable to external pressures that may influence their decisions. This lack of equilibrium in consultations fosters an inequitable environment where economic interests tend to overshadow the territorial and cultural rights of the communities.

Additionally, there is a recurring criticism regarding the lack of follow-up and effective enforcement of agreements made during consultations. Even when communities succeed in influencing decisions, the commitments made are frequently not honored, perpetuating a sense of abandonment and distrust. Without clear accountability mechanisms and independent oversight, prior consultations become a process without real consequences for companies or the government, reinforcing the perception that they are merely formalities rather than genuine exercises of justice.

The challenge of ensuring that legal pluralism does not remain merely symbolic

The reform also establishes the protection of the cultural and territorial heritage of communities, recognizing their normative systems and legal pluralism. However, this legal recognition presents several challenges that must be addressed to prevent these advancements from remaining merely symbolic. First, it is unclear how these systems will effectively interact with the national legal framework, particularly given that the constitutionally recognized legal pluralism in Mexico is unitary rather than egalitarian. It is not Indigenous peoples who establish their rules for engagement with the State; rather, it is the State, through Mexican positive law, that dictates them.

The coexistence of two legal systems could create tensions and conflicts regarding jurisdiction, especially in contexts where territorial rights and economic interests clash. Without clear mechanisms to harmonize Indigenous laws with national laws, this recognition risks becoming a declaration without significant practical impact. Moreover, intercultural justice requires comprehensive and committed training for judicial operators—including judges, lawyers, and public defenders—which has not been adequately addressed in the reform.

In terms of strengthening social cohesion, it is crucial to recognize that legal pluralism may, in some cases, exacerbate inequalities within communities. Not all communities possess the same capacity for organization or resources, which could lead to internal conflicts over the interpretation and application of their own normative systems. While the reform allows for greater control over territories, it must be accompanied by policies that promote equity within the communities themselves to prevent deepening existing asymmetries.

A reform that could be merely symbolic

In relation to climate justice, recognizing the territorial and cultural rights of Indigenous communities is a crucial component for environmental protection, as these communities have historically acted as guardians of biodiversity. However, this approach encounters tensions with the economic interests of the State and extractive companies, which continue to prioritize megaprojects without acquring the genuine consent of the affected communities. Climate justice can only be achieved if the voices and traditional knowledge of Indigenous communities are respected in decision-making processes regarding their territories, necessitating a profound shift in development policies.

Regarding gender equity, the reform includes provisions for the participation of Indigenous and Afro-Mexican women in decision-making. However, this progress is insufficient unless it is accompanied by concrete measures to ensure that these provisions are effectively implemented. Within communities, women face barriers both within their cultural contexts and in their interactions with the State, which calls for specific empowerment and support policies to guarantee that their participation is not merely idealized on paper. Achieving this will require the active involvement of Indigenous peoples as complex systems.

Historically, the Mexican State has granted formal recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights but has not committed to transforming the power dynamics that perpetuate exclusion and marginalization.

One of the most pressing issues is the lack of clarity regarding how the allocation of specific budgetary resources will be ensured to implement the recognized rights. Without adequate funding, the mechanisms for Prior, Free, and Informed Consultation could devolve into mere formalities, lacking genuine decision-making power for communities. Moreover, any promised autonomy could be rendered meaningless if communities do not have the necessary resources and infrastructure to manage their own projects.

Finally, there is a risk that the reform will remain a symbolic or rhetorical acknowledgment without profound structural changes. Historically, the Mexican State has granted formal recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights but has not committed to transforming the power dynamics that perpetuate exclusion and marginalization. Without a substantial shift in economic policies that prioritize extractivism and commercial interests, the reform’s impact could be significantly limited.

Elisa Cruz Rueda is both a lawyer and anthropologist. She is currently a professor at the School of Indigenous Management and Self-Development at the Autonomous University of Chiapas.